Newly published research from UCC is now showing that microplastics (plastic pieces smaller than 5mm) in our freshwaters are being broken down into even smaller nanoplastics (smaller than 1µm, at least five thousand times smaller in size) by a type of freshwater invertebrate animal, and that this may happen much faster than previously estimated.

With microplastics widespread in seas and oceans, their harmful effects on many different marine animals are well known. However, we know relatively little about the microplastics in our freshwater rivers, streams and lakes.

We still don’t know exactly where they come from, where they end up – and crucially – what damage they can cause if they get into our food chain.

Until now, breakdown of plastics had been thought to occur mainly through very slow processes in the marine environment such as sunlight or wave action, which can take years or decades.

But UCC researchers have discovered that a very common invertebrate animal found in Irish freshwater streams is able to rapidly breakdown these microplastics in just hours.

SIGNIFICANT FINDING

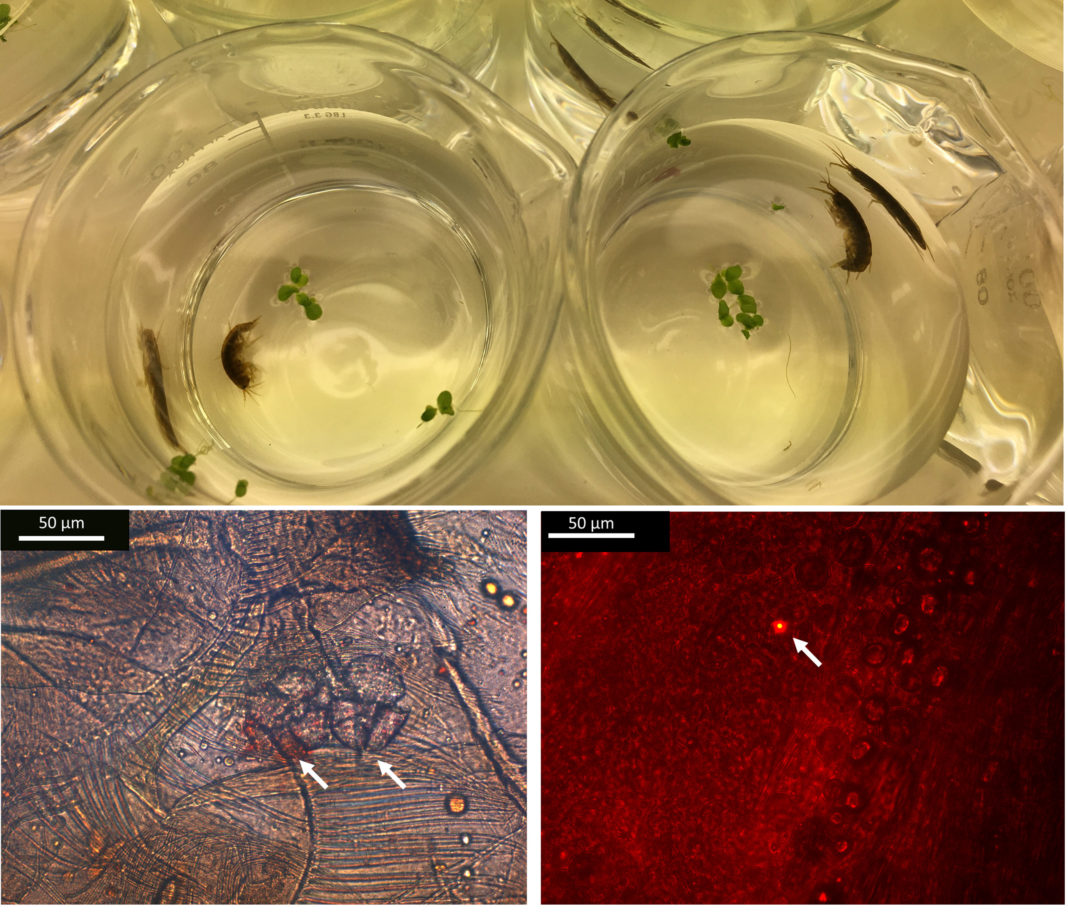

Study leader Dr Alicia Mateos-Cárdenas, of UCC’s School of BEES and Environmental Research Institute, said: “We have found that the freshwater amphipod, a small crustacean, called Gammarus duebeni is able to fragment microplastics into different shapes and sizes, including nanoplastics, in less than four days.

"Whilst this species lives in Irish streams, they belong to a bigger animal group of invertebrates commonly found around the world in freshwaters and oceans.

"Our finding has substantial consequences for the understanding of the environmental fate of microplastics.”

The alarming results of this EPA-funded study, published in Scientific Reports, also have consequences in terms of the impacts of plastics.

While microplastics can become stuck in the gut of seabirds and fish, current understanding suggests that the smaller nanoplastic particles, could penetrate cells and tissues where their effects could be much harder to predict.

The findings that such a common invertebrate animal can rapidly produce vast numbers of nanoplastics is particularly worrying for researchers.

“These invertebrates are very important in ecosystems because they are prey for fish and birds, hence any nanoplastic fragments that they produce may be entering food chains,” Dr Alicia Mateos-Cárdenas added.

“The data in this study will help us to understand the role of animals in determining the fate of plastics in our waters, but further research is urgently needed to uncover the full impact of these particles.”