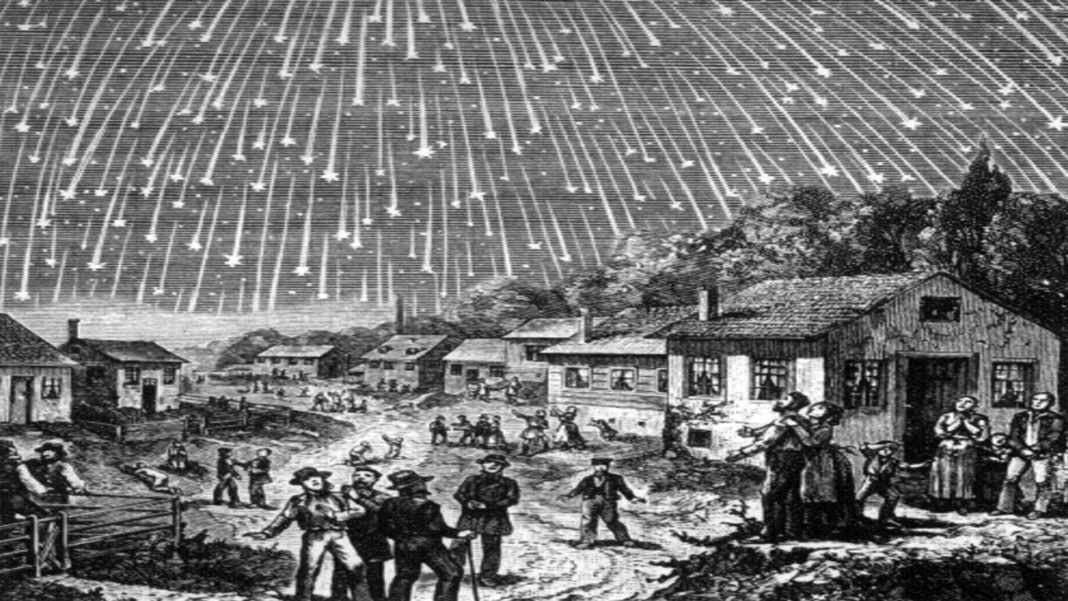

November 1833. As the night skies explode in blazing light over America’s Deep South, the slavers on one plantation – terrified of the end of the world – attempt to make restitution to those they have enslaved.

Every year, in mid-November, Earth passes through the Leonids, a huge meteor cloud associated with the comet Temple-Tuttle. Each year sees impressive displays, with the skies on some nights offering truly spectacular showers.

On the night of November 17, 1966, the Leonids gave what is considered one of the greatest meteor showers in living memory, with thousands of meteors per minute streaming through the atmosphere. Most years are not so dramatic, but if the skies are clear it’s always worth staying up. The phenomenon reaches its peak around the 17th or 18th of November and this year – weather permitting – Ireland should see many meteorites, as there will be no moon to spoil the show.

In November, 1883, the Leonids put on a display so spectacular that it is still remembered in the United States, 184 years later, as ‘The Night The Stars Fell’.

That night was immortalized in the 1930s jazz standard ‘Stars Fell On Alabama’, when the Leonid meteor storm was so intense many thought the world was ending.

“On the night of November 12-13, 1833, a tempest of falling stars broke over the Earth,” wrote the Victorian astronomy writer Agnes Clerke. “The sky was scored in every direction with shining tracks and illuminated with majestic fireballs. At Boston, the frequency of meteors was estimated to be about half that of flakes of snow in an average snowstorm. Their numbers… were quite beyond counting; but as it waned, a reckoning was attempted, from which it was computed, on the basis of that much-diminished rate, that 240,000 must have been visible during the nine hours they continued to fall.”

In his journal, Joseph Smith, founder of the Church of the Latter-Day Saints, noted the event as a clear sign that the coming of Christ was at hand.

One particularly affecting account of that night is that of Amanda Young, then a small girl living in slavery in Maury County, Tennessee, awoken in her cot by the sound of screaming.

“Somebody in the quarters started yellin’ in the middle of the night to come out and to look up at the sky. We went outside and there they was a fallin’ everywhere!

Big stars coming down real close to the groun’ and just before they hit the ground they would burn up! We was all scared. Some o’ the folks was screamin’, and some was prayin’. We all made so much noise, the white folks came out to see what was happenin’. They looked up and then they got scared, too.

“But then the white folks started callin’ all the slaves together, and for no reason, they started tellin’ some of the slaves who their mothers and fathers was, and who they’d been sold to and where. The old folks was so glad to hear where their people went. They made sure we all knew what happened … you see, they thought it was Judgement Day.”

‘Stars Fell On Alabama’ was written in 1934 by Frank Perkins, with lyrics by Mitchell Parish. The earliest-known recording was by the Guy Lombardo orchestra, on Decca Records on August 27, 1934.

The song was recorded by many fine artists, among them Billie Holiday, Bing Crosby, Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong, Cannonball Adderley with John Coltrane, Jack Teagarden, Jimmy Buffett, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Doris Day, Art Tatum, Stan Getz, Vera Lynn and Harry Connick, Jr.

In 2002, the phrase ‘Stars Fell On Alabama’ was added to Alabama licence plates.

If you stay up to see the Leonids this year, spare a thought for Amanda Young, a little girl preserved in the amber of history, but for all that still just a small child who couldn’t know the brutality and misery of the years ahead.

Amanda’s whole life was to be – in the eyes of the society in which she lived – no better than that of a farm animal, a human being who could be worked to death, or raped by her ‘owners’ or forced to ‘breed’ with other slaves.

Thanks to Amanda’s great-great granddaughter Angela Y. Walton-Raji, we know a little of Amanda’s life.

Ms Walton-Raji reckons her great-great grandmother was born in approximately 1826, making her seven or eight The Night The Stars Fell, the night the slavers acknowledged that the people they enslaved were people. Nothing focuses the mind more, apparently, than the prospect of the end of the world.

“Unfortunately,” Ms Walton-Raji writes, “it would be many years before Amanda would be free from enslavement, and she and her parents remained slaves until the Civil War ended. Perhaps the fear of Judgement Day may have kept Amanda and her family together, it will not be known.

“She was fortunate to have stayed with her family, and her children had not been sold from her. But this incident stayed with her.”

Amanda spoke, says her great-great granddaughter, “over and over, till her death in 1920” of that night in November 1833.

We’re all stories in the end, and I hope Amanda’s story had a happy ending.

One night, when Amanda was a little girl, she looked to the stars as the world ended and the white folks admitted their crime and begged for forgiveness.