Spanning 1,500 years of Irish life, and containing almost 11,000 biographies, the Dictionary of Irish Biography is now available free online.

If all politics is local, then perhaps all interest in history is slightly local too, and, if so, perhaps a look at local entries might be informative. With that in mind, I went looking through the treasure trove that is the Dictionary of Irish Biography (DIB) for mentions of my native Glanworth.

The DIB, a comprehensive online dictionary of almost 11,000 of the most famous people in Irish history, has been made available for the first time free to the public. There are some strict criteria surrounding qualification for inclusion in the DIB, which was launched in 2009 by the Royal Irish Academy.

“First and foremost, subjects eligible for inclusion must be dead (usually for at least five years) and must either be born on the island of Ireland or have had a significant career there,” writes DIB researcher Terry Clavin in the Irish Times. “Exiles (like James Joyce) are included as are blow-ins (like St Patrick), but not second- or more-generation emigrants of Irish extraction (like John F Kennedy), unless they resettle in the old country.”

Women have been poorly served by the DIB, only making up 10% of the original 2009 publication, something which Clavin says reflects the lack of opportunity for women in Irish society. That representation has more than doubled now, and Clavin says it will continue to improve, thanks in no small part to the growth in scholarship around women’s history. (The work of the Daughters of Dún Iascaigh history group in Cahir this month should be at the top of the DIB inbox.)

Recent additions include Violet Gibson, the Irishwoman who shot Mussolini, and Mary Young, the notorious pickpocket and crime boss immortalised as Jenny Diver in John Gay’s 1728 The Beggar’s Opera and then as Pirate Jenny in the 1928 The Threepenny Opera by Hauptmann/Brecht/Weill.

No assassins or crime bosses feature among the entries relating to Glanworth, but we live in hope of future additions.

There are six mentions of Glanworth in the DIB, and a strong religious theme runs through most of them. The first is in the biography of Bartholomew Crotty (1769–1846), president of Maynooth College, and Catholic bishop of Cloyne and Ross. Born in Clonakilty, Crotty is said to have been educated at “a classical school” in Glanworth.

Sculptor Gabriel Hayes (1909–1978) gets a mention for her 1944 bronze reliefs – a ‘Sacred Heart’ and a ‘Madonna and Child’ – commissioned for the side altars of Holy Cross church, Glanworth.

Youghal-born Church of Ireland clergyman and antiquarian Samuel Hayman (1818 – 1886) had his first posting as a curate in Glanworth, and in 1846 he organised a famine relief committee in the parish. Described as a shy, retiring scholar, Hayman would later suggest that the Famine had been a divine punishment for the growth of Mariolatry (excessive veneration of the Virgin Mary, something very much frowned upon in Protestant circles). That said, Hayman was also known as a compassionate and generous man who ministered to the dying in a cholera outbreak in Youghal in 1849, and who never thought twice of sharing his academic findings with antiquarians of different faiths.

John O’Brien (Seán Ó Briain) (c.1701–1769) was born in the townland of Ballyvoddy, in Rockmills, “about 5km north of Glanworth”. Due to the Penal Laws, O’Brien was forced to study for the Catholic priesthood overseas, entering the Irish seminary in Toulouse in 1725, and going on to study further in Paris after his ordination in 1731. O’Brien returned to Ireland in 1738, serving as parish priest in the united parishes of Castlelyons and Rathcormac. Three of his sermons survive in the Royal Irish Academy.

Appointed bishop of Cloyne and Ross in 1748, O’Brien gained a reputation as a disciplinarian and a reformer, and he published in 1756 a book of regulations for priests in his diocese “notable for the emphasis it placed on catechesis, its determined opposition to clandestine marriages, and – a sure sign of a micro-manager – the large number of sins that were reserved for episcopal absolution”.

In August 1758, O’Brien placed Mitchelstown and its surrounding environs under interdict, essentially shutting it down for religious rites, when a dispute about a clerical appointment turned violent. This led to Lord Kingston issuing a warrant for the bishop’s arrest, and offering a reward of £100.

In 1762, O’Brien excommunicated those involved in the Whiteboys, denouncing them as a “dangerous contagion”. Suffering from ill health, O’Brien left Ireland for France in 1767, where his English-Irish dictionary Focalóir Gaoidhilge-Sax Bhéarla was published in 1768.

Bishop Seán Ó Briain died 13 March 1769 at Lyon and was interred in the church of Saint-Martin d’Ainay. His tomb was destroyed during the French revolution.

The first line of the biography of John Joseph Therry (1766–1853) reads: “commissioner of revenue, was the first son of James Therry of Castle Therry, near Glanworth, Co. Cork, and his wife Elizabeth (née Nagle), who appears to have been a first cousin of Edmund Burke (qv), whose mother Mary was a Nagle of Ballyduff, Co. Cork”.

The first Catholic to hold high office in the central administration after the relief acts of the 1790s, Therry was appointed commissioner of revenue in 1806, with Lord Grenville, who confessed to not having “ever heard of his name before”, although he was “thought the fittest Roman Catholic for that situation”.

Therry was a cousin of Daniel O’Connell, his maternal uncle Nicholas Nagle (d. 1787) having married Honora O’Mullane, whose sister Catherine was mother of the Liberator.

Then there’s Gerald de la Roche (c. 1200-1262), a nobleman who married one of Thomas fitz Anthony’s daughters, making him a claimant on fitz Anthony’s Munster lands, a claim de la Roche forfeited as a result of his support for Richard Marshal, earl of Pembroke, in 1234.

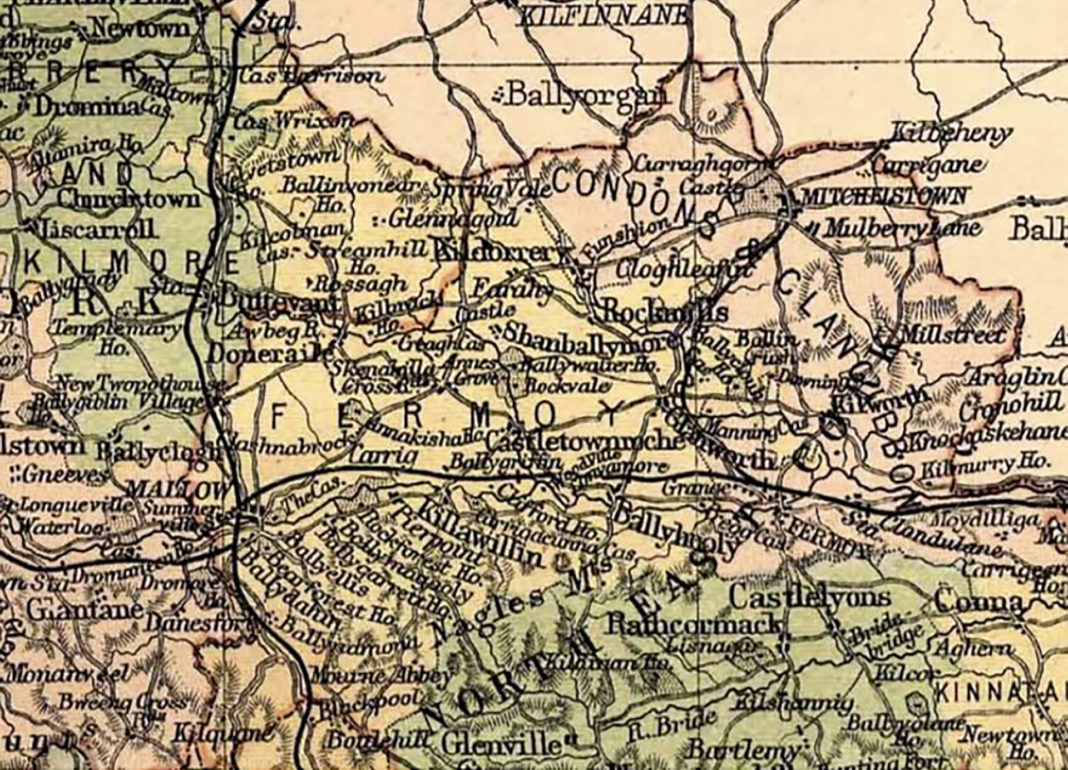

De la Roche arranged a marriage between his grandson David and Amice, daughter of William de Caunteton (Condon), bringing Glanworth into the Roche lordship carved out of the old cantred of Fermoy, sparking a long feud between the Roches and the Condons.

In 1262 de la Roche joined an army led by Richard de la Rochelle against the MacCarthys and was killed in the wake of the Battle of Callan, which occurred in the modern-day Healy-Rae barony.

De la Roche’s importance within the Anglo-Norman lordship was recognised by the Gaelic annalists who called him the “third best baron in Erin”; and his family’s importance was acknowledged by Henry VII in 1489 when David Roche was recognised as Lord Roche.

And that’s just Glanworth.

The DIB contains 14 articles mentioning Kilworth, among them biographies of Lady Catherine Louisa Morgan, and – of course – William Brennan, the highwayman Brennan on the Moor himself. (I can never think of Willie Brennan without remember the late Liam Clancy – eyes twinkling, flashing and glowering – recalling to me Bob Dylan robbing that tune for Bob’s own “Rambling Gambling Willie”. Liam is in the DIB. Proper order.)

There are 59 mentions of Mitchelstown in the DIB, featuring names like Edward Carson, Agnes Ryan, Bram Stoker, and of course John Mandeville. William Trevor isn’t in the DIB, but that’s only because he died in 2016. Give it another year or so.

There are 112 mentions of Fermoy. The town’s founder, John Anderson features, of course, as does his son, Sir James Caleb Anderson, on whom a baronetcy was bestowed in 1813 in honour of his father. Thomas William Croke, Catholic archbishop of Cashel and the man who gave his name to Croke Park, is there, in his capacity as president of St Colman’s College, Fermoy. Thomas Caeannt, who gave his life for Ireland, and his name to Fermoy’s bridge, is featured, as is Liam Lynch. Novelist Kate O’Brien is featured, but sadly there is no mention of the much-lamented Fermoy pub named in her honour.

The DIB archive is an astonishing resource, and I suspect you might find it a valued companion, and not just in lockdown. Happy reading.