Perhaps, in the final analysis, Stan Lee was neither hero nor villain. Perhaps he was that most Marvel of characters, an anti-hero, writes Donal O’Keeffe.

I was saddened last week to hear of Stan Lee’s passing, at the age of 95. He was someone who has been a small part of my life since I was a child.

In Ireland in the late 1970s, it was next to a miracle to find an American comic, and we had to – for the most part – make do with black-and-white British reprints. But when you were lucky enough to locate a real American comic, it was like finding gold.

The best part of Marvel Comics was always that whenever you came in, you entered in the middle of an ongoing story of costumed heroes set in a shared universe, part of which featured real-life locations, none of them more important than New York City.

If Spider-Man, in his own comic, needed scientific advice beyond his own expertise, he might swing over to the Baxter Building, home of the Fantastic Four, to ask Reed Richards, Mr Fantastic, for help. While Spidey and Reed might have a chin-wag in the lab, Reed’s brother-in-law, Johnny Storm, the Human Torch, might drop in and mention that last week he and Spider-Man fought Mysterio in a battle on Coney Island.

A helpful asterisk would lead the reader to a boisterous footnote from Marvel editor-In-chief Stan Lee, directing the reader to the relevant issue of Marvel Team-Up, currently on sale, wherein the Torch and Spidey beat the tar out of a weirdo wearing a fish-bowl on his head. Maybe in the background, poor Ben Grimm, trapped in his monstrous, orange, rocky form, might think to himself that he and Spidey took down the mob boss Silvermane recently. Another footnote would direct the reader to the current issue of Marvel Two-In-One.

As the slogan of Marvel’s 21st Century cinematic universe goes, “it’s all connected”.

When I was small, every Marvel comic had an introductory paragraph on the top of the first page, and each of them instanced Stan.

The other day, I opened some of my long boxes and fished out some of my old comics – that caramel smell of old paper! – reminding myself of those breathless, brilliant blurbs.

“While attending a demonstration in radiology, high-school student PETER PARKER was bitten by a spider which has been accidentally exposed to RADIOACTIVE RAYS. Through a miracle of science, Peter soon found that he had GAINED the spider’s powers… and had, in effect, become a human spider

“Stan Lee presents: THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN!”

“A brilliant scientist – his best friend – the woman he loves – and her fiery-tempered kid brother! Together they braved the unknown terrors of outer space, and were changed by cosmic rays into something more than merely human!

“MR FANTASTIC! THE THING! THE INVISIBLE GIRL! THE HUMAN TORCH! They are the FANTASTIC FOUR – and the world will never again be the same!

“Stan Lee presents: THE FANTASTIC FOUR!”

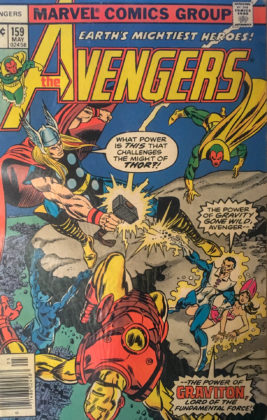

“And there came a day, a day unlike any other, when Earth’s mightiest heroes found themselves united against a common threat. On that day, the Avengers were born – to fight the foes no single hero could withstand! Through the years, their roster has prospered, changing many times, but their glory has never been denied! Heed the call, then – for now, the Avengers Assemble!

“Stan Lee presents: The Mighty Avengers!”

“Caught in the heart of a Nuclear Explosion, victim of Gamma Radiation gone wild, Doctor Robert Bruce Banner now finds himself transformed in times of stress into seven feet, one thousand pounds of unfettered Fury… the most powerful creature to ever walk the earth…

“Stan Lee presents: The Incredible Hulk!”

“CAPTAIN AMERICA & BUCKY! THE SUB-MARINER! THE ORIGINAL HUMAN TORCH & TORO!

“During the darkest days of World War Two, these five heroes have banded together as THE INVADERS… to battle the Axis Powers to the death, in the name of freedom!

“Stan Lee presents: THE INVADERS!”

The Invaders was a minor enough comic from the 1970s, featuring new, war-time adventures of characters created in the 1930s and ‘40s – the so-called “Golden Age of Comics” – for Marvel’s precursor, Timely Comics. That’s where Stan Lee had come in.

Timely Comics was founded in 1939 by Martin Goodman, who was born in 1908 to Lithuanian Jewish immigrants. Working out of a grimy lower Manhattan office, Goodman’s specialty was pulp magazine knock-offs, and he churned out romance, westerns and detective stories which sold at 15 cents per issue.

A year earlier, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster (both the 23-year-old sons of Jewish immigrants) had sold a story called “Superman” to National Allied Publications for $130. Debuting in Action Comics Number 1, Superman became a smash hit, regularly selling half a million copies.

National’s sister company, Detective Comics, launched Batman, and suddenly superheroes were big business. Ever a man to spot a trend, Goodman jumped on the bandwagon.

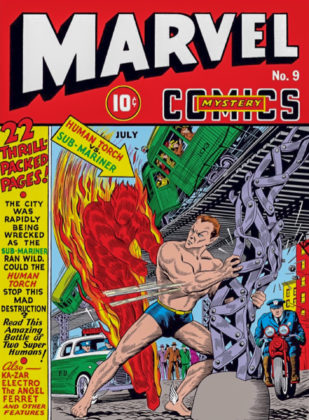

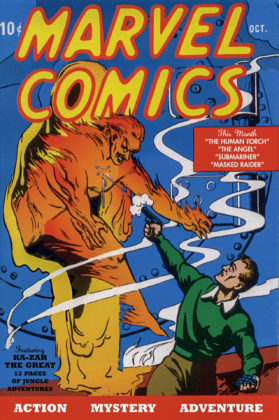

Timely Comics was a shoe-string, bargain basement sweatshop, populated by writers and artists who were either waiting for an opportunity to move to better things or who couldn’t get work anywhere else. Timely’s first comic, Marvel Comics Number 1, featured the work of two 21-year-olds, Carl Burgos (born Max Finkelstein, the son of Jewish parents) and Bill Everett (a descendant of William Blake).

As Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics The Untold Story puts it, Burgos and Everett kept it simple, focussing on fire and water. Burgos came up with a story about a greedy scientist creating an android, a synthetic man, with a single flaw: it would burst into flames on contact with air. Thus was born the original Human Torch.

Everett, already an alcoholic and a 60-a-day smoker, created Prince Namor, the Sub-Mariner. Pointy-eared, pointy-eyebrowed, and widow’s-peaked, Namor was immediately a departure from the superhero template. Wearing only swimming trunks, the amphibious heir to Atlantis was violent, volatile, and perpetually ready to be offended. In short, he was the first Marvel anti-hero, and the antecedent to the likes of Wolverine, Black Widow and Punisher.

It’s often said that Stan Lee revolutionised comics by introducing to them in the 1960s the frisson of interpersonal conflict. The truth is the Torch and Namor were punching the heads off each other, fire versus water, two decades before Stan thought to have the Fantastic Four bicker amongst themselves.

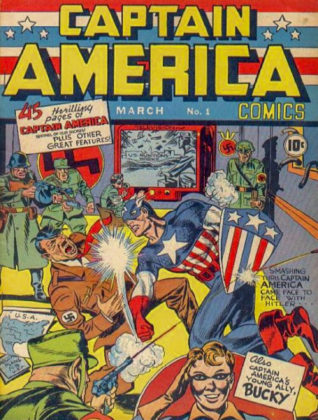

Into the Timely mix came Jacob Kurtzburg. At the time a jobbing artist, the man who would one day be known as Jack Kirby was a once-in-a-century genius. In 1940, he teamed up with writer-editor Joe Simon to create the patriotic superhero Captain America.

Simon and Kirby, two first-generation Jewish immigrant kids, went for broke: the cover of Captain America Number 1 – released in December 1940 – showed Cap punching a real-life super-villain on the jaw. A year before the United States entered World War II, Captain America clocked Adolf Hitler. It sold a million copies.

Joe Simon said he and Kirby were promised 25% of Captain America’s profits. Believing Goodman was cheating them, they negotiated a secret plan to jump ship to National. Goodman got wind of their plan, and Simon and Kirby suspected he was informed by his wife’s cousin, a very young production assistant named Stanley Lieber.

Originally employed as 'a gofer', Lieber, the son of Romanian Jewish immigrants, would soon graduate to writing text stories and back-up features. Dreaming of a career as a novelist, for his comics work he used the pen-name, 'Stan Lee'.

Entering the US Army in 1942, he served in the Signal Corps within the United States, until 1945, when he returned to Timely. The popularity of superheroes waned after the war, and Timely, now known mostly as Atlas Comics, turned to Westerns, sci-fi, romance, horror, funny animals and whatever else seemed to be selling for other companies.

As the ‘fifties frittered away, Atlas found itself greatly reduced, and a thoroughly-disillusioned Stanley Lieber was forced to fire his staff of artists.

By 1961, Stan was ready to quit. He had never got around to writing that novel, and he was feeling the breath of forty on his neck.

According to Lee, ever an unreliable narrator, his boss, Martin Goodman, came back from a round of golf with Jack Liebowitz, publisher of DC Comics, the company National and Detective had become. Liebowitz had bragged of their new smash hit, The Justice League of America. It was a team book, featuring some of DC’s most popular characters – among them Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and revamped versions of the Flash and Green Lantern.

Goodman ordered that Stan steal this idea and create a new team of superheroes. Not exactly enthused, Lee told his wife, Joanie, that he was going to resign. She changed his mind, he claimed, suggesting he write it the way he wanted.

“I wrote an outline containing the basic description of the new characters and the somewhat offbeat storyline and gave it to my most trusted and dependable artist, the incredibly talented Jack Kirby.”

Kirby remembered it differently: “I would say that’s an outright lie.”

According to Kirby, “Marvel was on its ass, literally, and when I came around, they were hauling out the furniture… Stan Lee was sitting there crying. I told them to hold everything, and I pledged that I would give them the kind of books that would up their sales and keep them in business.”

The Fantastic Four was unlike anything ever seen on the newsstands, although Kirby would later note the similarities to his previous DC series The Challengers of the Unknown.

Reed Richards was a genius scientist, and his best friend, pilot Ben Grimm, was a rough but decent street brawler. Reed was in love with Susan Storm, (and so was Ben, but that tends to be forgotten now), and when Richards decided to launch an unauthorised rocket into space – to beat 'the Reds' – Sue insisted her teenaged brother Johnny tag along.

Passing though a band of cosmic rays as they cleared the atmosphere, the four astronauts crashed back to Earth and were transformed.

Reed became a pliable, rubber band of a man, and Ben became a Jack Kirby monster, an orange, rock-skinned tragedy. Sue was rendered invisible, which probably said more about the gender politics of the early 1960s than either author intended. Johnny became a recycled, teenaged version of Carl Burgos’ Human Torch character.

The difference with these characters was they bickered and fought. As the English author Alan Moore would note cuttingly, decades later, Stan Lee’s characters had an edge which gave them a second dimension. In fact, it still remains an open question whether they were really Stan Lee’s characters at all.

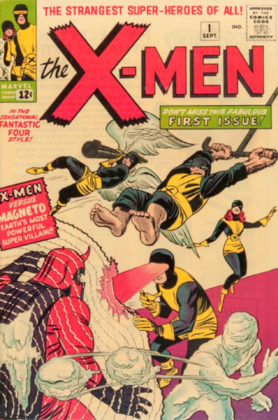

The Fantastic Four was a hit, and in issue 4, Namor the Sub-Mariner returned, now far closer to a villain than a hero. Kirby and Lee soon followed up on their success, with characters such as the Hulk, Thor, Iron Man, Ant-Man and the Wasp, heroes who would band together as the Avengers. In Avengers Number 4, Captain America was revived for the modern age, a man out of time. The X-Men soon followed, another Kirby creation, as were the Black Panther, the Inhumans, the Eternals, and a hundred others.

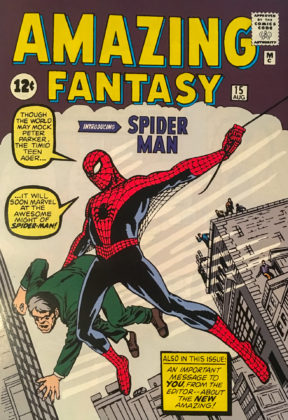

In August 1962, in Amazing Fantasy Number 15, a character which would forever become synonymous with Lee made its debut.

A skinny, angst-ridden high-school nerd, Peter Parker became the wisecracking, wall-crawling Spider-Man. Artist Steve Ditko crafted stories which balanced finely between superhero action and teenage soap opera. Peter was bullied at school by the football jocks, and bullied at work by his boss, and he struggled to support his ageing aunt, get a date with Betty Brant, and save the city from the Green Goblin.

Stan Lee added dialogue which gave Spider-Man a rich inner life. Readers loved what they were seeing, and suddenly comics became popular with an older, college-aged readership.

Ditko also created for Marvel Doctor Strange, Master of the Mystic Arts.

The 'Marvel Method', whereby Stan Lee would provide the artist with a sketchy plot, and the artist would then work out the story and return the finished pages for Stan to add dialogue, caused considerable irritation with the artists, who – having done all the heavy lifting, would then see Stan Lee getting the writer’s credit.

For the genre-defining, three-part 1966 Fantastic Four saga, where an angelic herald, the Silver Surfer, selects Earth as the next meal for the planet-eating celestial giant Galactus, Stan’s entire initial creative input had reputedly been to furnish Jack Kirby with the four word instruction: “Have them fight God”.

Steve Ditko eventually demanded credit for the plotting he was contributing to Amazing Spider-Man, and starting with Number 25 (June 1965), Ditko received plot credit for the stories. However, the increasingly right-wing Ditko and the liberal Lee were no longer on speaking terms, and Ditko quit after issue 38 (July 1966).

In a 2010 deposition, Ditko’s Amazing Spider-Man successor artist, John Romita, stated that Lee and Ditko “ended up not being able to work together because they disagreed on almost everything, cultural, social, historically, everything, they disagreed on characters…”

Ditko went back to Charlton Comics, where the pay was lousy, but the artists were given greater freedom. He would work for DC, and return to Marvel, too, and he continued to work into the 2000s. The reclusive Ditko died on June 29, 2018, at the age of 90.

One day in the summer of 1966, Carl Burgos’ daughter Susan saw him haul his entire comic collection into his backyard and burn it. In his book, Sean Howe notes that Burgos was at the time attempting to sue Marvel over the copyright to the Human Torch.

“I grew up believing that he came up with this fabulous idea,” Burgos’ daughter said, “and that Stan Lee took it from him.”

In the August of that year, Fantastic Four Annual Number 4 featured the return of Burgos’ original, android Human Torch. The issue appeared precisely 28 years after Marvel Comics Number 1, exactly as the initial, 28 year copyright on the character was expiring. In the comic, the original Torch is revived to fight his modern-day counterpart and the rest of the Fantastic Four, and is then killed off again, living just long enough to ensure Marvel’s claim to the character.

Howe speculates that it was this which prompted Burgos to destroy his collection.

In the early 1970s, Burgos denounced comics as a 'terrible field', saying “If I had known how much trouble and heartbreak the Torch would bring me, I would never have created him.”

Burgos died in 1984, aged 67.

Around the same time Carl Burgos was burning his comics, and extinguishing the original Human Torch, Bill Everett, creator of the Sub-Mariner, found himself suddenly getting as much work with Marvel as he wanted. Legend has it he received a loan from Martin Goodman, one which he need not repay, so long as he didn’t sue.

Everett died in 1973, aged 55.

Joe Simon, too, was making noises about a copyright claim, in this case on Captain America. In an effort to secure Marvel’s ownership of the character, Goodman ran reprints of Golden Age Captain America strips, without crediting Simon and Kirby. Goodman then told Jack Kirby that Simon was trying to claim sole credit for Cap’s creation.

In a corner, Kirby took a deal. In return for a promise that Marvel would give him a matching amount to any future settlement with Simon, Kirby signed a deposition stating: “I felt that whatever I did for Timely belonged to Timely as was the practice in those days. When I left Timely, all of my work was left with them.”

In 1989, an embittered Jack Kirby told the Comics Journal how much it irritated him when people spoke of his “collaboration” with Stan Lee: “Stan Lee and I never collaborated on anything! I’ve never seen Stan Lee write anything. It wasn’t possible for a man like Stan Lee to come up with new things – or old things, for that matter. Stan Lee wasn’t a guy that read or told stories.”

Jack Kirby created or co-created much of what would one day become the largest cinema franchise in history – by 2017 earning approximately $13 billion – and, like Carl Burgos before him, he regretted much of it.

“I should have told Stan to go to hell and found some other way to make a living, but I couldn’t do it. I had my family, I had an apartment. I just couldn’t give all that up.”

On February 6, 1994, at the age of 76, Jack Kirby died of heart failure.

Stan Lee attended the funeral, with the permission of Kirby’s widow Roz. Toward the end of the ceremony, Lee slipped quietly away. Roz saw him go, and called out to him, but he didn’t hear her.

Marvel was shamed into giving Roz a pension, and she vowed to live long enough to claim every cent she believed Jack was owed. She died four years after Jack.

In 2014, Marvel agreed with Kirby’s estate to honour “Mr Kirby’s significant role in Marvel’s history”.

Stan Lee succeeded Martin Goodman as Marvel publisher in 1972, a role he held until 1996, after which he received an annual million-dollar stipend as chairman emeritus. In 1980, he moved to California and set up an animation studio, narrating The Incredible Hulk and Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends TV shows, and he spearheaded Marvel’s Hollywood ambitions. Lee’s first on-screen cameo was in the popular live-action TV version of The Incredible Hulk (1978-82). Most Marvel movies contained a Stan Lee cameo.

A gifted self-publicist and a fine judge of artistic talent, Stan Lee was a champion of the 'work-for-hire' system, which saw young artists sign away their creations for a pittance. He was also an entertainer and showman who used his vast platform to gently promote progressive causes, not least of them the Civil Rights movement.

As the figurehead of an entertainment behemoth, Stan Lee’s legacy is monumental, but it will be forever tainted by the shabby way in which those who worked with, and for, him were treated, and by the shameless way in which he denied full credit to the artists whose creations made him both rich and famous.

He put the superhero – and, in all those cameos, himself – centre-stage in popular culture, but he did so at a terrible cost to the artists who created the superhero.

If Martin Goodman might be caricatured as the villain of the Marvel story, then perhaps Stan Lee was that most Marvel of characters, the anti-hero.

Stan Lee died a year after the passing of his beloved wife Joan Boocock. They were predeceased by their daughter, Jan, who died in 1953. She was three days old. He is survived by his brother, Larry Lieber, and by his daughter Joan Celia (JC).

Stan Lee: December 28, 1922 to November 12, 2018.