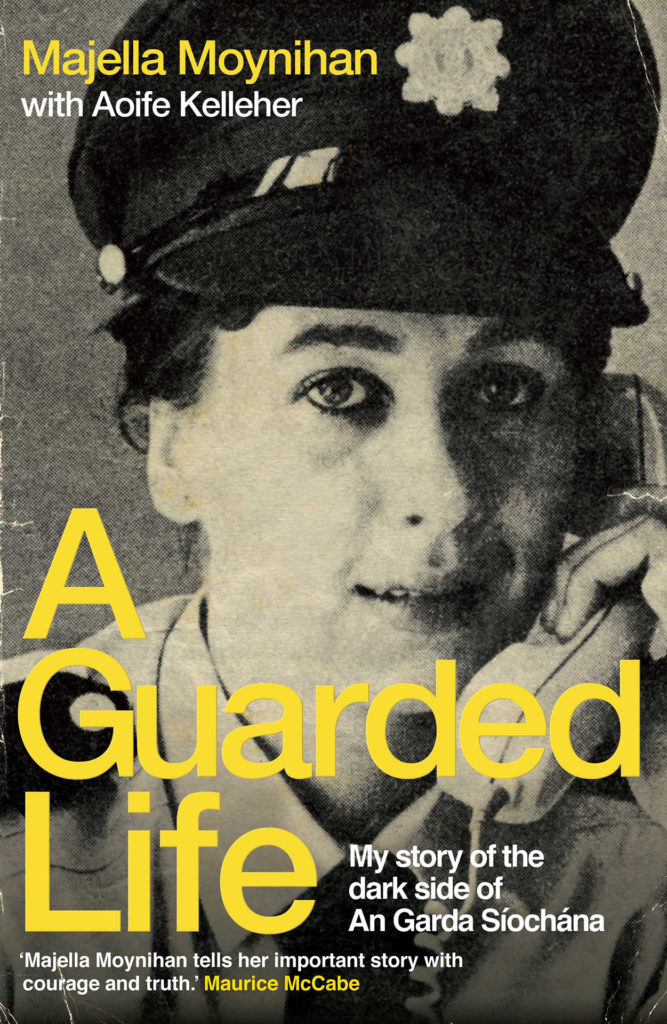

Former Garda Majella Moynihan – who says she is the only person in the world to be charged with giving birth – talks with Donal O’Keeffe about feeling pressured into giving up her baby, about the book she has written, and about the bullying and misogyny she experienced in An Garda Síochána, in an Ireland all too recent.

Shortly after 6.30pm on Tuesday, 23rd October, 1984, 22-year-old Recruit Bangharda – as female gardaí were called then – Majella Moynihan was on the beat in central Dublin when she received a message over the radio: “Majella, return to the station, please.”

Back in Store Street Garda Station, she was directed to an office on the second floor, where a visiting senior garda, Chief Superintendent TP Corbett, told her he was the investigating officer in a disciplinary case he was preparing against her. He then issued her with a caution she herself had often given to suspected rapists, burglars and assailants: “You are not obliged to say anything unless you wish to do so, but anything you do say may be written down and used in evidence against you.”

Majella Moynihan was a vulnerable young woman who had just given up her baby against her wishes, alone in that room with a senior garda officer. He was angry and aggressive, subjecting her to a series of inappropriate and deeply personal questions. Was the father of her child the first man with whom she had had sex? How long were they together? When had they commenced sexual relations? When had they had sex? Where? Had they used condoms? How had she become pregnant?

Nine days after this meeting, Majella was charged with two counts of misconduct under garda discipline regulations: that she, “being an unmarried, female member [of the force] did associate on terms of intimacy and undue familiarity” with an unmarried male garda, “had sexual intercourse with [him and, later gave] birth to a male child at Galway Regional Hospital”. She was further accused of “conduct likely to bring discredit on the force [by giving] birth outside wedlock”.

That night, Majella cut herself for the first time.

“If I sit down and think about the severity of those two charges, I can honestly tell you the tears come to my eyes and they can’t stop. They degraded me so low and I don’t know how I got back up.

“There are no words to describe what they did to me. There are no words. I can speak and speak and speak, but nobody knows what went on in my head, nobody knows the torture I went through.”

The father of Majella’s child, a recruit garda she had known since before their time together in the Garda Training College in Templemore, had deserted her in the early days of her pregnancy. In the book, he’s referred to as “Fintan”, although that is not his name. Initially, without discussing things with Majella, he had asked her father for her hand in marriage.

“I nearly lost my life,” Majella says. “There was no way I was going to marry that man.

“And then he decided to walk away. I stood my ground. I think his mother put the doubt into him as to whether he was the father – which he definitely was.

“He ran from his responsibilities. He just ran. Even if he had just supported his child, and me, things would have been some way different. See, I had nothing. I had no solid ground at all.”

The Archbishop intervenes

In Store Street, rumours circulated that Majella was to be dismissed. Majella went to Mena Robinson, the woman who had arranged – via the Catholic crisis pregnancy agency Cura – the adoption of Majella’s baby boy.

Shortly afterward, she says, Archbishop Kevin McNamara of Dublin interceded with the then Garda Commissioner Larry Wren, telling him that firing her would send a message to other pregnant unmarried female guards that they would be better off traveling for abortions. “If you sack Majella, you’ll open the gates for England.” (The late Commissioner Wren’s family disputes this account.)

In February 1985, Majella was called to Harcourt Square – garda headquarters for the Dublin metropolitan region – and given a formal caution: “If it happens again, Bangharda Moynihan, you’re sacked.”

Two months later, Majella was taken to Letterkenny Garda Station, where she was interrogated in front of a sworn disciplinary inquiry into the behaviour of the father of her child. He was to be represented by a member of the Garda Representative Association. The GRA general secretary, Jack Marrinan, had already declared publicly: “I am the father of a young lady myself – I wouldn’t like anybody to think [a bangharda becoming pregnant outside of wedlock] would be considered as the normal condition or appropriate behaviour.”

Majella was alone.

Sitting in a chair in the centre of the room, she faced three senior garda officers seated at the top table. Apart from a stenographer, she was the only woman in the room.

The questioning was brutal, and humiliating. The insinuations about Majella’s character were appalling, and sickening. It is honestly difficult to read what she was put through.

While Majella had been charged with two offences – having sex outside of marriage, and giving birth to a baby – the father of her child was only charged with one offence, having sex outside of marriage.

“I am the first person in the world to be charged with giving birth,” Majella says.

Fintan’s representative did everything in his power to not just cast doubt on whether Fintan and Majella had even had sex, but to suggest that if they had, he was only one of many men to have done so, and thus may not have been the father of her child. One particularly offensive moment saw Majella accused of naming her baby David, not, as she had said, after the Star of David, but rather after an entirely fictitious former lover.

Ultimately, Fintan was given a fine, something which seems preposterous now.

“He was fined £90,” Majella says. “And I was torn apart by misogynist bastards within An Garda Síochána.”

Sister Claire Caples

Majella tells me that it is her honest belief that had she come from a supportive family background, things might have been different, but that was not to be, because when she was 18-months-old, her mother was killed by a hit-and-run driver, and Majella was taken from her home in Banteer, Co Cork, and placed in St Joseph’s Industrial School in Mallow.

“I wouldn’t have been aware of anything at the time, I was only a baby, but when I was young, I do remember the biggest thing that I felt was the abandonment, and I’ve lived with that for so many years. Was I good enough, was I loveable? It was all my own self-doubt.

“I feel a lot of children who were in institutions felt that we weren’t worthy, and that really was something that I brought with me through my life, and when the episode happened to me with the gardaí, that just reawakened it all for me again.”

Majella says her first eleven years were very happy, thanks to Sister Claire Caples, who was then the head of the industrial school.

“Sister Claire Caples was a dote. I’ll never come across anyone like her again in my life. She was from Kildorrery in Co Cork.” (Majella pronounces it “Kildollery”. I tell her that’s what a lot of locals call it.)

“Sister Claire was the best example to me of what a mother should have been. She made that role so beautiful for me. She’d tip you on the head and that was her way of saying ‘You’re great, and you’re special’.

“Everybody had the height of respect for her. We just loved her. She just had a beautiful gentle way. When she retired, the ties were cut too soon.”

“When Sister Claire left, I was 11 or 12. I was devastated. It was like another person was gone out of my life again, another abandonment. I don’t mean Sister Claire abandoned me, she didn’t, but I felt abandoned.”

Majella says that children, especially children in an institution, rely on the happy memories to see them through tough times.

“If anybody showed any kindness to us, it was saved away.” She says that all ended when Sister Claire retired. “And then I saw the real meaning of growing up in an institution.”

“We were nothing. And (we were told) how lucky we were to be there. I don’t know how lucky I was to be beaten consistently, and to be told I was nothing and to be constantly called names.”

A child’s wish for justice

Majella believes that what happened her in Mallow shaped the rest of her life.

“I was a child that was just reaching out to be loved, and I was a child that felt so differently to everybody else, and a child that I believe never excelled to my full potential because I didn’t have that nurturing that I required, and it was an extremely lonely place.

“It was really, really lonely, and the beatings were horrific.”

Majella remembers one nun once banged her head off a radiator four times because she was late for study. “One of the girls who was there with me told me recently ‘I can still hear you screaming, Majella’.

Majella says she was bullied constantly.

“I’m a strong person, but I was broken in there.”

She feels that her desire from an early age to join the gardaí came from a child’s wish for justice, and a longing to help vulnerable people.

“When the pain starts in your childhood, it consumes you until you can cut that tie, and it’s a very, very hard thing to do. It took me many, many years of counselling to see that I wasn’t the problem. I was handed to the State and the Mercy nuns failed in their duty of care to me.”

On the phone, Majella Moynihan is a warm and friendly person, and she starts many sentences in our conversation by calling me by my name. “Well, Donal, as you know…” “You know it yourself, Donal…” “Donal, you know the way women are treated…” It’s a disarming, and endearing, trait. I find myself thinking she would have been a great community guard, even before she tells me of her experiences as a community guard.

“I was a community guard in Dun Laoghaire for a period of time, I was coming toward the end of my career in the guards at that stage, so really mentally I wasn’t that great, but I knew that I had it, and I knew that if I had been supported in that role I would have actually fulfilled a major part of my dream of becoming a garda.

“It was within that aspect of my time in the gardaí that I felt I was doing the real work, the work that was to me the basic work. That was treating human beings with kindness, and listening to their stories and being there for them, and letting them know that they could pick up the phone and ring you at any time.”

A forced adoption

Majella believes she was forced into giving David up for adoption, and she says she was put under horrendous pressure. There is a chilling moment in A Guarded Life, the book Majella has written with her friend Aoife Kelleher, when Majella realises that Mena Robinson of Cura, the Catholic crisis pregnancy agency, who has been nothing but kind to her, is not her friend at all.

“Not at all. She just wanted my baby. When I came to that realisation, I then saw the collusion between the gardaí and the Catholic Church. All they wanted was the child and they never once thought of the mother. Never, ever, was my well-being discussed.

“It was always ‘Sure how can you keep your child? Your father doesn’t even know.’ It was always ‘You’re 21-years-of-age. I’ll get a good family for your child.’

“In the vulnerable state of mind I was in, I was in no fit state to sign an adoption paper.”

Majella says she spent her pregnancy in a state of loneliness and confusion.

“The first time I went to the doctor was in February 1984, when I was already six months pregnant, so I had gone all those months without even visiting a doctor.

“I was so out of it. I was completely living outside of my body. I just did not know what was going on. I did not know. I was so alone. So alone. And it’s not loneliness, it’s that I was utterly alone in the world.

In Galway Regional Hospital, on May 30, 1984, after a very difficult labour, Majella gave birth to a beautiful baby she would have christened David. Later, in the nursery, she asked to be allowed to hold him. “Oh no,” said the nurse in attendance, “you can’t”.

All these years later, Majella says, she can still see that nurse’s face.

“My heart was wrenched. To look in at my own flesh and blood and to be refused to hold him.”

“I could have just gone”

Those years were very difficult for Majella. Ostracised within the gardaí, Majella was subjected to appalling bullying and sexual harassment, including two serious sexual assaults.

“My mental health was so fragile. I could have just gone. I could have just taken my life, because of that isolation, that shame, and that guilt that I felt. And then to be told that I had demoralised the garda force, that’s a horrible thing to tell a 22-year-old.

“For me, the most horrific part of my story is that I was alone all the time. I had no support whatsoever, in relation to the job that I had joined believing that I would have support in becoming the guard that I wanted to be.”

Majella says she can never forgive the gardaí who hurt her.

“They destroyed my life. The shame that I carried for so many years because of An Garda Siochana. They’ll never give me back those years. They’ll never give me back my freedom. They took my freedom. They took my personhood. They took my son. They took my life. They took my job. They took everything that I possessed. They took my vocation. They took everything.

“And the hardest thing for me to do was to get my head right, and to get peace of mind back in between my two ears, and for me to accept that my son was gone for adoption, because of them.”

Given her own experiences within the gardaí, and her experience with the Garda Representative Association, Majella is scathing of the supports offered to gardaí.

“Being a garda is an extremely tough job, and if you’re not getting the support from within, where are you getting it? No wonder so many guards drink. No wonder so many guards take drugs. No wonder so many guards are in trouble, because there is nothing there for them.

“I can tell you that the 21-year-old girl who became pregnant and who was treated so appallingly by An Garda Siochana, has only healed in the past two years.”

A garda culture of misogyny and prejudice, and the loss of her baby to an adoption she felt pressured into, left Majella heartbroken, relying heavily on alcohol, and, after a number of suicide attempts, hospitalised in St John of God’s psychiatric hospital.

“Mentally, I was gone. I couldn’t see beyond the pain. I remember screaming out. Screaming. Please somebody help me. It was like ten claw-hammers pounding in my head. I couldn’t stop it, and it was all self-hatred.” Years of counselling have since helped her reclaim her life.

In 1994, Majella met the man she would later marry, another garda, and they would have a son together, Stephen. Although their marriage has broken up in recent years, Majella says her former husband is a kind man, and a model father. Their son is the centre of her world.

“Stephen is powerful! He just brings joy to my heart. He’s a lovely, compassionate, gentle, kind, loving young fella. He has great empathy, and great understanding.”

Majella Moynihan left An Garda Síochána in 1998. She says: “It was the best decision I ever made”.

“It was like a light switched on”

A few years back, Majella went to a one-woman show about adoption in the Civic Theatre in Tallaght. There was an after-show audience discussion, and to her own surprise, Majella stood up and spoke, telling the hushed crowd that she had been charged with giving birth.

“It was the first time I had ever told my story, and it was like a light switched on.” As a result, Majella was introduced to film-maker Aoife Kelleher, and together they made a powerful and heart-breaking RTÉ Radio 1 documentary, which aired last June.

The documentary, and a subsequent radio interview with Sean O’Rourke, led to public outrage, and Majella received an apology from Garda Commissioner Drew Harris, and from the then-Justice Minister Charlie Flanagan.

Majella says her son Stephen listened to the documentary. “He said ‘Oh Mammy, I’m so proud of you’. He healed me a lot.”

I ask Majella if she has had any contact with Fintan, the father of her son, David.

“I spoke with Fintan before the documentary aired and he said ‘Leave the fucking past in the past’. I thought ‘Yeah. You get fined £90 and you’re telling me to leave this in the past?’ I said to myself there’s no way I’m leaving the past in the past, because I knew this story had to be told.”

Now Majella has written a book with Aoife Kelleher. It’s a harrowing and engrossing read, and a grim reminder of an Ireland all too recent, an Ireland harsh, misogynistic and sex-obsessed, the Ireland that martyred Ann Lovett, Joanne Hayes and Eileen Flynn.

“I always did say that I had a book in me, but I didn’t think I’d ever have the courage to do it, but now I’m no longer carrying the shame. The book for me is freedom.”

In recent years Majella has been reunited with her son, David.

“He’s 36 now. He’s a lovely guy, but he has his demons.”

Majella is hopeful that in time they can have a normal relationship.

“I still feel so guilty for giving him up. I felt abandoned all my life, and there’s a part of me that can’t forgive myself for signing that dotted line.

“What galls me is that they had such power over me. I wish I hadn’t allowed them take my son.”

Majella says that through all she has endured, her faith has sustained her.

“I don’t know how I got through it, but I still have great faith that there’s someone looking after me. I can honest-to-God say that my faith got me through. Now, don’t get me wrong, I wouldn’t be a holy Mary or anything like that, but I have great faith that there’s something better, something greater.

“I have to look at my life and what I came through, and I have to believe that somebody has helped me through this.”

A Guarded Life: My Story of the Dark Side of An Garda Siochana by Majella Moynihan with Aoife Kelleher Hachette Ireland €14.99