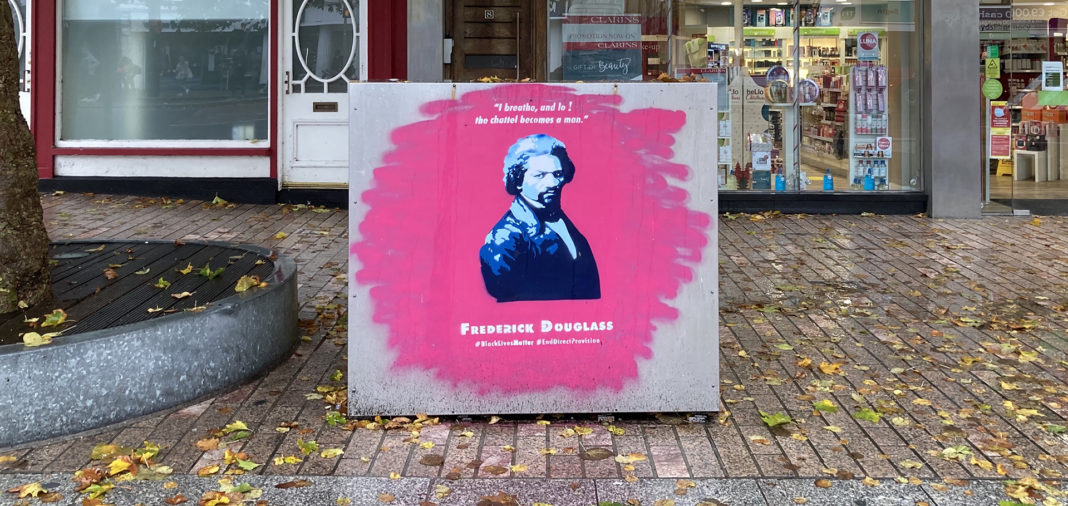

There’s a lovely piece of street art on Cork’s Grand Parade, on the electrical box outside Lloyd’s Pharmacy, featuring a striking portrait in blue of Frederick Douglass against a bright pink background.

The mural bears a famous quote from the American abolitionist: “I breathe, and lo! the chattel becomes a man”, and beneath it the hashtags #BlackLivesMatter and #EndDirectProvision.

The painting is by Kevin O’Brien, co-founder of the volunteer art group Mad About Cork, who told The Echo in June that he was struck by the resonance between Frederick Douglass’ “I breathe” and the last words of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man who was killed in Minneapolis in May when a police officer knelt on his neck for almost nine minutes.

“There’s a striking contrast to the last words of George Floyd which have since become a powerful slogan of the Black Lives Matter movement – ‘I can’t breathe’,” O’Brien said. It’s a potent and clever juxtaposition, and it works well in conjunction with Frederick Douglass’ connection with Cork, and Ireland.

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born into slavery, most likely in his grandmother’s cabin, on a plantation on the Eastern Shore of Chesapeake Bay in Talbot County, Maryland, sometime in February 1818.

“The opinion was … whispered that my master was my father; but of the correctness of this opinion I know nothing,” Douglass wrote in 1851. “My mother and I were separated when I was but an infant … common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age.”

Escaping on a northbound train at the age of 20, and later falling in love with a freed woman, he took the surname Douglass, and soon became famous for his brilliant anti-slavery writing and mesmerising oratory. He was also an advocate of temperance, having seen how slaveholders dulled the spirits of slaves by plying them with alcohol at Christmas and other holidays.

Douglass became a leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York, and he would, in time, be called a friend by Abraham Lincoln, with the president telling him publicly in the packed East Room of the White House: “There is no man in these United States whose opinion I value more than yours”.

When Douglass’ autobiography, The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, was published in 1845, his friends advised him to leave the country. The book revealed his real name, and concern grew that his former “owner” might attempt to retrieve his “property”. Slave-catchers, who abducted freed people and escaped slaves and sold them south, were a real worry to Douglass.

Douglass embarked on a two-year lecture tour of Britain and Ireland, arriving in Dublin in late August. There he met and befriended Daniel O’Connell, himself a passionate campaigner against slavery. Then seventy, and displaying what has been called his characteristic “affable arrogance”, O’Connell introduced the 27-year-old escaped slave to a spellbound audience in the Conciliation Hall on Burgh Quay as “the black O’Connell of the United States”.

Douglass was met with loud cheers when he told the crowd that he had first heard the name of O’Connell in the “curses of his masters”, and he said that O’Connell’s condemnation of slavery had “a great effect” in America.

“For, while with one arm the Liberator was bursting the fetters of Irishmen, with the other he was striking off the literal chains from the limbs of the Negro.”

As Laurence Fenton puts it in his invaluable Frederick Douglass in Ireland: The Black O’Connell, “Douglass would always speak well of O’Connell; the same was not true of the other major Irish figure with whom he would spend time: Father Theobald Mathew”.

Having spent a month in Dublin, Douglass then travelled down through Wexford and Waterford, before arriving in Cork, where he would stay for more than three weeks.

Laurence Fenton describes in vivid detail an event which took place on the evening of Monday, 28 October, 1845 in the Temperance Institute on Academy Street. With the South Main Street Quadrille Band playing from the balcony, and a crowd of over 250 people assembled, Father Mathew – the Apostle of Temperance – welcomed the 27-year old Douglass to the stage.

Douglass had heard of Father Mathew in America, and he had seen him administer the temperance pledge to a crowd of a thousand in Booterstown, but when he met Mathew in Cork, they quickly became friends.

Douglass later wrote of the welcome he received in Cork: “Amongst them all, I saw no one that seemed to be shocked or disturbed at my dark presence. No one seemed to feel himself contaminated by contact with me. I think it would be difficult to get the same number of persons together in any of our New England cities, without some democratic nose growing deformed at my approach. But then you know white people in America are whiter, purer and better than the people here. This accounts for it!”

The next morning, Douglass visited Mathew’s house on Cove Street, with the 55-year-old Mathew rushing out to welcome his guest as he approached. “Welcome! Welcome, my dear Sir, to my humble abode.” Douglass would recall that Mathew’s home was indeed humble, uncarpeted, and containing very little furniture.

“The breakfast table was set when I went in,” Douglass recalled. “A large urn stood in the middle, surrounded by cups, saucers, plates, knives and forks … all of a very plain order … too plain, I thought, for so great a man.”

Douglass was hugely impressed with Mathew: “His whole soul appeared to be wrapped up in the temperance cause … His time, strength and money are all freely given to the cause; and his success is truly wonderful.”

Even though Douglass had been teetotal for eight years, he proudly took the pledge from Mathew. “He … gave me a beautiful silver badge. I now reckon myself with delight the fifth of the last five of Father Mathew’s 5,487,495 temperance children.”

Douglass’ friendship with Father Mathew would end in 1849, when the Apostle of Temperance, on a tour of America, declined an invitation to attend an anti-slavery rally in Worcester, Massachusetts. Not wishing to antagonise American anti-abolitionists, Mathew said: “I have as much as I can do to save men from the slavery of intemperance, without attempting the overthrow of any other kind of slavery.” He also appeared to suggest that nothing in the Bible prohibited slavery.

Douglass wrote: “Nothing reveals more completely … the all-prevailing presence … of slavery in this land, than the sad fact that scarcely a single foreigner who ventures on our soil, is found able to withstand its pernicious and seductive influence … We had fondly hoped, from an acquaintance with Father Mathew, that his would be a better fate; that he would not change his morality by changing his location … We are however grieved, humbled and mortified to know that HE too, has fallen.”

Douglass “wondered how being a Catholic priest should inhibit him from denouncing the sin of slavery as much as the sin of intemperance.” Douglass said he felt it his duty to “denounce and expose the conduct of Father Mathew.”

On January 1, 1846, as he prepared to leave Ireland after four months, Douglass wrote of his earliest experiences of Ireland.

“Instead of the bright, blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft, grey fog of the Emerald Isle. I breathe, and lo! the chattel becomes a man.

“I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab – I am seated beside white people – I reach the hotel – I enter the same door – I am shown into the same parlour – I dine at the same table – and no one is offended.

“I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people. When I go to church, I am met by no upturned nose and scornful lip to tell me, ‘We don’t allow n*****s in here!’”

In June, Kevin O’Brien told The Echo that Douglass “describes Ireland as being full of compassion and respect, and a safe refuge.

“With the Black Lives Matter movement and anti-racism protests taking place across the world, now is probably a good time for all of us to look again at racism and prejudice in our own country,” O’Brien said.

“How do we treat black people and other minorities, Travellers, asylum seekers, and poor people here? Unfortunately, not all would share Douglass’ sentiments today, but for me there is hope in his words.”

When Frederick Douglass was in Cork, he stayed with the Jennings family on Brown Street. The Jennings were a wealthy Unitarian family and they owned a factory which made such products as mineral oil, vinegar and soda water.

Brown Street doesn’t exist anymore. It’s under the Paul Street Shopping Centre now, and on the front of that building, on Rory Gallagher Place, not far from Geraldine Creedon’s beautiful sculpture “Tribute”, there’s a plaque commemorating Richard Dowden (1794 – 1861) “Co-founder of the Temperance Movement, poet and botanist. Mayor of Cork in 1845. Managed Jenning’s (sic) soda-water factory which stood near here.”

It’s less than a ten-minute walk across town from Brown Street to Father Mathew’s house at 8 Cove Street. The tall young African-American would have strolled past the site of the former Carey’s Lane Chapel, where construction had already been under way for six years on the red sandstone and limestone building which would, eleven years later, be consecrated as Saints Peter and Paul’s Church.

Further along, he would have crossed the South Channel of the River Lee at Parliament Bridge, or at the South Gate Bridge – the Nano Nagle footbridge was 140 years away – but perhaps on his way to Cove Street, Frederick Douglass rounded the corner of Patrick Street, onto the Grand Parade, and passed by the spot where Kevin O’Brien’s portrait of him would sit, 175 years in the unimaginable future.