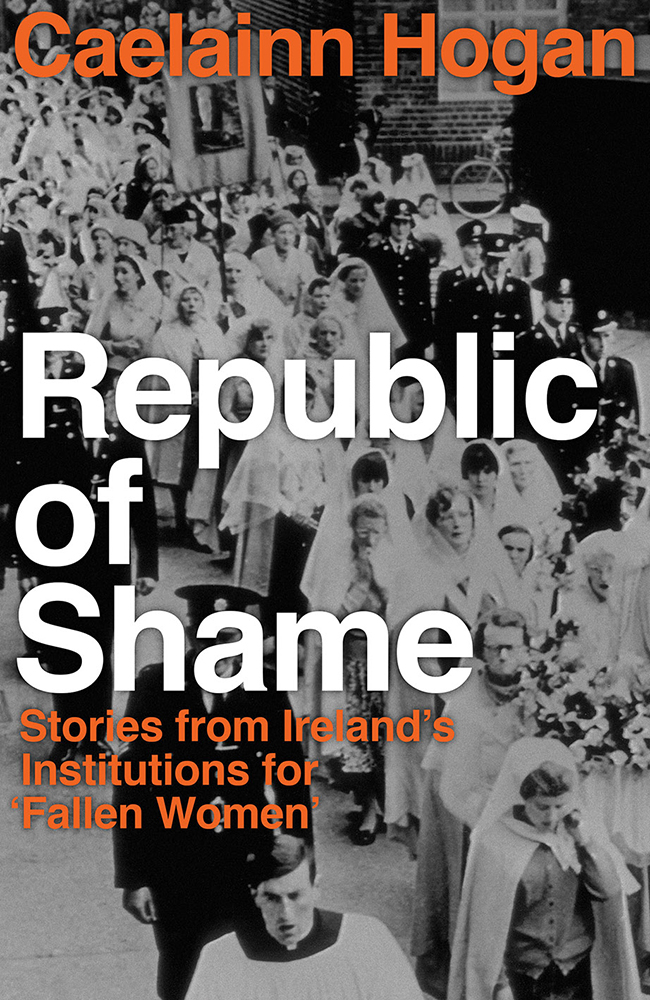

Caelainn Hogan’s extraordinary debut book, Republic of Shame, gives a voice to the survivors of Ireland’s interconnected web of Magdalene Laundries, mother and baby homes, and forced adoptions. She talks with Donal O’Keeffe.

Last month, Margaret Atwood tweeted about Caelainn Hogan’s Republic of Shame, noting how “alarmingly recently, the Catholic Church, working in concert with the Irish State” operated a network of Magdalene Laundries, mother and baby homes, and a system of forced adoptions.

Referencing her own most famous book, the best-selling author and feminist icon added: “At least in The Handmaid’s Tale they value babies, mostly. Not so in the true stories here”.

I asked Hogan how she felt about such an endorsement. She replied that Atwood has long been aware of her book, and of what Hogan calls Ireland’s shame-industrial complex.

“When she was in Dublin earlier this year, while holding a copy of my book on stage, Atwood spoke about how control of reproductive rights and of children has been a hallmark of totalitarian regimes,” Hogan said.

“Since then she has tweeted about the book a few times, shedding light on the treatment of children in Ireland’s religious-run institutions and reminding us of the parallels around the world, such as the stolen babies during Argentina’s military regime, which the Catholic church was also involved in.

“Her dystopia of Gilead highlights the very real injustice of separating children from their mothers and how it is used as a means of social control.”

The final report of the Mother and Baby Home Commission of Investigation is due in February. Its findings are certain to be harrowing, and preliminary estimates released by the Government last month reveal that far in excess of 190,000 women and children were incarcerated in institutions between 1922 and 1998.

There is a wonderful, introductory blurb on the back of Hogan’s book, one which really encapsulates a book which examines a dark and very recent time in Irish history, the effects of which we are still living through and the legacy of which we are right now attempting to reconcile.

“None of the building blocks of the shame-industrial complex were intrinsically Irish or intrinsically Catholic. But independent Catholic Ireland brought them to a sort of dark perfection.”

Caelainn Hogan is clearly someone who genuinely cares about the survivors of Magdalene laundries and mother and baby homes, to the extent that she routinely travels the length and breadth of the country to attend lonely commemorations often populated only by people deliberately forgotten and ignored.

Hogan was born in Dublin, in 1988. I asked why she felt she needed to write a book about issues which, some might say, are ancient history to someone her age. She rejected my suggestion, saying these are matters very much of our time.

“I knew I had to write this when I realised that I lived around the corner from a ‘holding centre’ for children awaiting adoption, run by the Sisters of Charity,” she told me. “One of the first adoptees I spoke to had been kept there as baby.

“Also, when I met Ann O’Gorman, a mother who gave birth in Bessborough, and is still searching for where her baby is buried, it hit home then how urgent it is that people get the answers they deserve and how painful the ongoing silence of those in the religious orders is.”

Hogan says the realisation that these institutions were not ancient history spurred her on.

“This was the Ireland I grew up in. I was born in 1988. My parents weren’t married at the time. The legal status of illegitimacy had just been abolished the year before but there were still institutions run by nuns where unmarried women were sent to give birth in secret, their children taken from them for adoption.

“As soon as I began speaking to people for the book, I realised I knew people personally whose lives had been impacted by these institutions. The aunt of a close friend of mine was sent to a mother and baby home the same year I was born.”

Hogan began writing her book in 2017, as test excavations in Tuam revealed that significant human remains were found in sewerage chambers on the grounds of the Tuam Home. She says this, coupled with the Repeal referendum, saw a national conversation about the shame imposed on pregnant women in Ireland.

Hogan says it felt like an important time to document the experiences of survivors of an institutional system that ostracised and incarcerated women and their children for so long.

“When I was writing this book, I came to realise that in Ireland almost all of us will know someone affected by the religious-run institutions. The separation of mothers from their children and the legacy of shame imposed on women in Ireland has a generational impact.

“For me the most important responses to the book have been from people who have shared their own stories, reaching out to tell me about their own experiences or what happened to people they know.

“When survivors say they feel heard through the book, that means everything. I’m only sorry I couldn’t include more people’s stories.”

Hogan notes that the recent interim Commission of Investigations report describes the affidavit supplied by Bessborough’s Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary as “speculative” and “misleading”.

She adds: “the religious sisters have given no clear answers as to where these children were laid to rest. I accompanied Carmel Cantwell to the famine graveyard in Carr’s Hill where she was finally told her brother William was buried, after years of searching and requesting records. I walked through that overgrown field with her, trying to find any marker or headstone. There was nothing there to mark the burial place of a child.”

More than 900 children died at Bessborough, but the burial records of only 64 are known.

“There was no respect shown for the lives of these children, even in death.”

Hogan feels survivors and their families will continue seeking the truth until there is finally transparent access to records and people have the right to their own identity.

“I think it’s important that the people impacted by these institutions are heard. Almost every survivor I spoke to expressed the importance that future generations understand what happened to them, to have their lived experiences are taught in schools.”

She says survivors and their families are the ones who have broken the silence around what happened in Ireland’s institutions and what, to some extent, is still happening today. She says she believes that Ireland’s direct provision system is making the scandals of tomorrow.

Republic of Shame is a superbly written work, and it deserves to sit on bookshelves alongside books like Mary Rafferty’s Suffer the Little Children, Mike Milotte’s Banished Babies, Alison O’Reilly’s My Name is Bridget, and the Tuam Babies book that Catherine Corless absolutely has to write, and Conall Ó Fathartha’s definitive Bessborough, which he also will get around to writing any day now.

This is Caelainn Hogan’s first book. She has set the bar very high for her second.

Republic of Shame, by Caelainn Hogan, is published by Penguin Ireland and is in bookshops now.