By Donal O’Keeffe

Imagine the scene. A rape trial. A young woman says she met a man at a nightclub and they kissed. She says she was drunk and he offered to walk her home. When they got to her place, she says she told him she was grateful, but she did not want to have sex. She says he then raped her.

He says they had sex, but it was consensual.

At the trial, Counsel for the Prosecution asks the accused man if he went to the nightclub with the intention of having sex.

Counsel asks the accused man how he was dressed on the night. Was he wearing tight clothing which accentuated the curves of his body, or perhaps showed a bit of flesh?

Was he walking with a swagger? Did he boast to the lads of his sexual prowess? Had he bragged to his friends that he was intent on getting 'the ride' tonight?

Counsel then asks if the accused wore a pair of novelty boxer shorts on the night? Did those boxers bear the legend 'Sex Machine'?

Then, in a move which causes the accused man to become visibly upset, Counsel for the Prosecution produces a pair of boxer shorts bearing the phrase 'Sex Machine'. Counsel for the Prosecution then presses the accused man, asking him repeatedly: “Did you go to that nightclub with the intention of having sex?”

It’s a preposterous scenario, and it could never happen. An accused man would never be subjected to such treatment during a rape trial. Right to a fair trial. Presumption of innocence. That sort of thing.

And there’s also still an ocean of difference between the way society treats the sexuality of men and the sexuality of women, and those attitudes inform the thinking of juries.

At the start of November, The Irish Examiner reported that the defence counsel in a Cork rape trial had asked the jury to take into account that the 17-year-old complainant had worn a thong with a lace front on the night in question.

“Does the evidence out-rule the possibility that she was attracted to the defendant and was open to meeting someone and being with someone,” Elizabeth O’Connell SC is reported as stating in the Cork Circuit Criminal Court.

Ms O’Connell is further reported as having told the jury, which later acquitted the accused man: “You have to look at the way she was dressed. She was wearing a thong with a lace front.”

In protest, Ruth Coppinger TD produced a thong in the Dáil, leading to international coverage of the case and its aftermath. Coppinger called for an immediate end to what she called 'routine victim blaming' in court.

Elizabeth O’Connell SC did not, as has been reported erroneously in international media, produce a thong in court. It is important to note that Ms O’Connell’s client was acquitted – which means he was found innocent of the charges against him – and this column accepts that result, and passes no further comment upon it.

During the Belfast rape trial of Paddy Jackson and Stuart Olding earlier this year, a thong worn by the complainant was introduced into evidence in court. Jackson and Olding were later acquitted.

In 2002 in Scotland, during the trial of a 15-year-old boy for raping 17-year-old Lindsay Armstrong, Lindsay was made – three times – to hold up her thong and to read aloud the slogan on them which said 'Little Devil'.

The accused was found guilty.

Two weeks after the trial, Lindsay took her own life.

As #ThisIsNotConsent trended globally, news of the Cork trial reached Ayrshire in Scotland.

“I am shocked this kind of thing is still being used as evidence,” Lindsay’s mother Linda told The Daily Telegraph. “I learned about the case when a friend sent the story to me. It brought all the bad memories back.

“I just thought I can't believe they are still bringing this up.”

Last Wednesday, RTÉ’s Mary Wilson spoke with Linda on Drivetime. It was a harrowing listen, with Linda clearly depressed and upset, and, with characteristic decency, Mary Wilson cut the interview short.

In the Dáil, as the cameras cut away from her – deputies are forbidden from using props – Ruth Coppinger said: “It might seem embarrassing to show a pair of thongs here in the incongruous setting of the Dáil, but the reason I’m doing it: How do you think a rape victim or a woman feels at the incongruous setting of her underwear being shown in court?

“And when is this Dáil going to take serious action on the issue of sexual violence?”

Justice Minister Charlie Flanagan, who is a solicitor, was unequivocal in his comments, saying it was his belief that there are no circumstances in which the clothing worn by an alleged victim should be taken into account.

“Clothes don’t rape women,” he said. “Rapists rape women.”

The Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar, thanked Deputy Coppinger for her powerful intervention, and said: “Let me say this, and let there be no doubt about it, nobody asks to be raped, and it’s never the victim’s fault. It doesn’t matter what you wear, it doesn’t matter where you went, who you went with, or what you took, whether it was drugs or alcohol.

“Nobody who is a victim of sexual violence, nobody who is a victim of rape is ever to blame for the crime which is committed on them.

“And I believe that any defence on those lines is absolutely reprehensible. And let me put that very clearly on the record of this Dáil.”

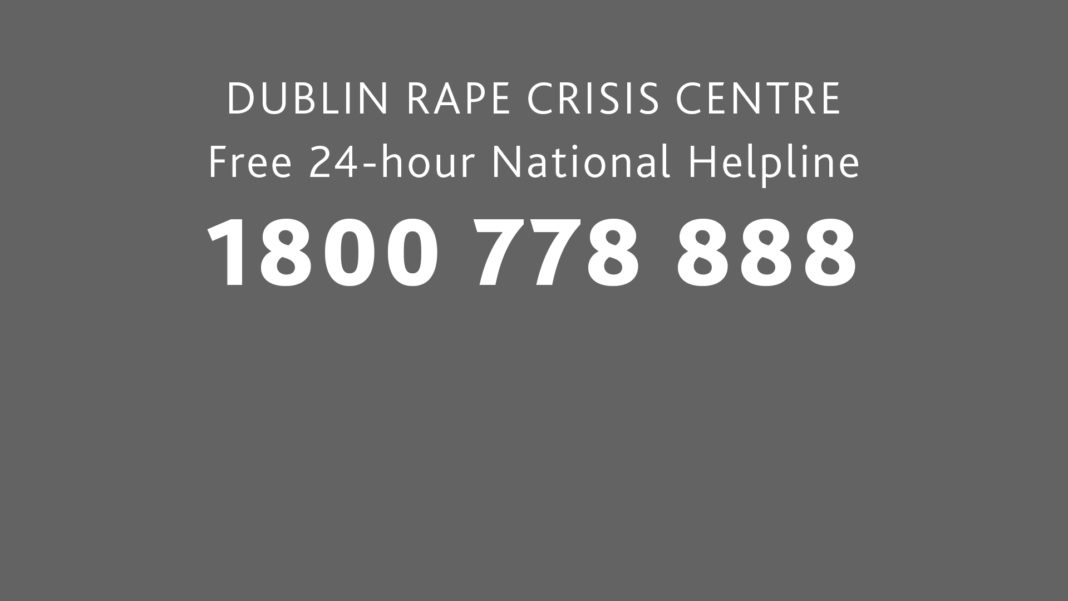

In 2017, 647 rapes were reported to the Gardai, an increase of 134 on 2016. 94% of complainants were women. 12,855 people contacted the Dublin Rape Crisis Centre’s free 24-hour national helpline on 1800 778 888, making last year its busiest to date.

Men suffer rape and sexual assault, too, but it is difficult to imagine a male complainant being questioned on his attire.

Last week, Charlie Flanagan said he wants “full-blooded” defence tactics used during rape and sexual assault trials to be re-examined as part of a wider courts review to be published next month.

It shouldn’t be too much to hope that, in time, the idea of a complainant being questioned on their clothing will seem as ludicrous as the same thing happening to someone accused of rape.

Dublin Rape Crisis Centre’s free 24-hour national helpline: 1800 778 888