It’s simply not good enough to argue we cannot judge the crimes of the past by the standards of today, writes Donal O’Keeffe.

Peter Mulryan was born in the Regional Hospital in Galway, on June 29, 1944. Six days later, he was sent to the Tuam Mother and Baby Home.

“My mother was kept there for 12 months after I had been born,” Peter told TG4’s documentary series Finné last week. “She slaved there, worked there, cleaning floors, cleaning babies – not necessarily her own baby – feeding other babies … The reason for that, we found, was in case we’d bond, in case the mother and child would bond … so they’d keep them separated.”

I’ve met Peter Mulryan a few times, and he’s a gentleman, and a gentle man. He has an air of kindness about him, and an innate decency which defines the man. I’m honoured to know him. Any heart with an ounce of love would break at Peter’s memories, and his every word to Finné burns with the unmistakeable clarity of truth.

Looking back on his earliest years, Peter recalls a bleak time, presided over by the Bon Secours nuns in Tuam. “The only memories I’d have, the area was so grey, grey stones and buildings. The scene never changed. My environment wasn’t changed, I never came outside them four walls for four-and-a-half years.”

Historian Catherine Corless, who in 2014 uncovered evidence that the remains of as many as 796 children might be buried on the site of the Tuam Mother and Baby Home, in a disused Victorian sewage treatment system, also spoke with Finné.

“I vaguely remember the Home Children – I think there was about four in the class I was in – in the Mercy Convent in Tuam. We didn’t play with them, because they arrived in later in the morning, always ten minutes later or so, and in the evening, then, they would leave earlier, and even at lunchtime they were kept apart from the rest of us.

“We just learned, you don’t talk to these children. They were always cold-looking, they didn’t talk, and they always had this frightened look about them.”

The Finné documentary on Tuam is a superb film, and its author, Louise Ni Fhiannachta, is to be commended for her work. It’s available on the TG4 Player, and I would thoroughly recommend you take a look. (click the TG4 logo)

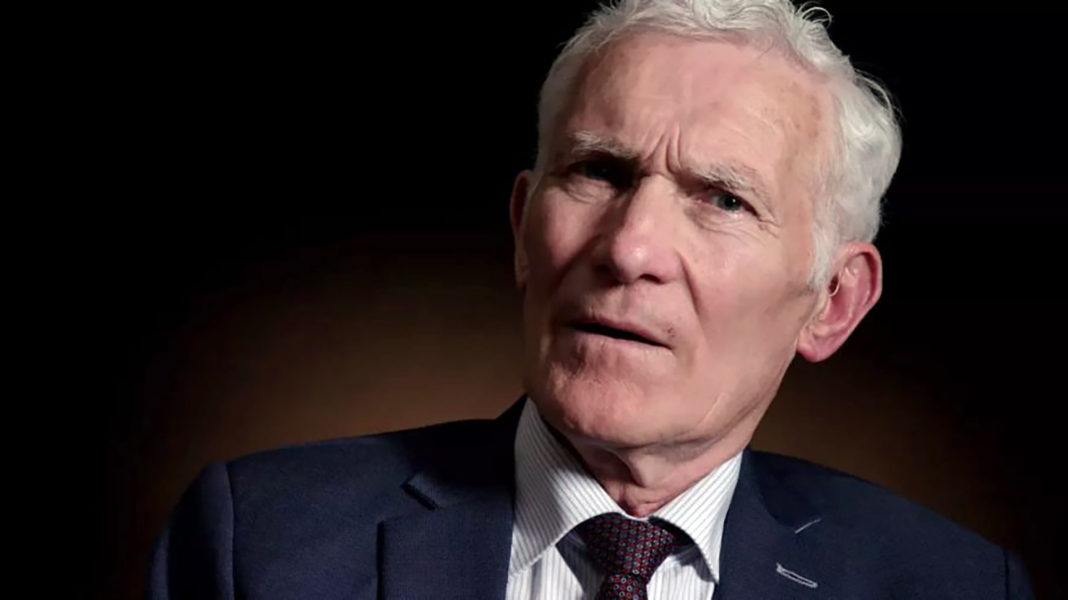

The film features a lengthy contribution from sociologist and Catholic priest, Father Mícheál MacGréil. He offers a counterpoint to Peter Mulryan and Catherine Corless, arguing against what he perceives as the “persecution” of the Bon Secours order.

“They think the blame lies with the individual. It doesn’t. Most of the people’s behaviour is based on the culture and the structure of the time. As far as I’m aware, the nuns arrived in order to help those girls because before that they ended up in the poorhouse or even out on the road.

“If you read Dickens or Hardy you’ll see the system that existed. Capitalism was growing. In order to sustain the economic system and pass wealth from one generation to the next, you had to be legitimate. And legitimacy was so important that people even went to such lengths that they were willing to abandon their beautiful daughters.

Peter Mulryan recalls being fostered out from the Tuam Home to work on a farm. Beaten brutally every day for imaginary sins, Peter was a tiny, malnourished boy, not toilet-trained, and forced to live in filth.

“It was so bad that if I took my pants off, it would stand up beside me, because it wasn’t cleaned. I had hair-lice as well, and that was very itchy and very uncomfortable.”

Peter recalls nights after he had been beaten, looking to the stars, and wondering where he came from, and always being drawn to the west. He would discover years later that was where his mother was.

In his early 30s, Peter met a young woman named Kathleen, and they fell in love. To get married, he needed a birth certificate.

“When I got the long birth cert … we discovered the parish, and found my mother’s name. Oh my God. ‘Twas a big shock to discover I had a mother.”

Peter and Kathleen went to that parish, and that house, and Peter says they met a man there they immediately recognised as Peter’s relative: “Everyone could see he was a relation of mine anyway. Yeah. The features. And then a woman came, who happened to be an aunt of mine, and she had all the features as well.”

Peter says he was terrified that his mother might have passed away, but his aunt told him his mother was in the Magdalene Laundry in Galway. Catherine Corless says mothers were sent from mother and baby homes to the Magdalene Laundries if they had a second baby. She notes this was State policy.

When Peter was reunited with his mother, he met a stooped, frail, damaged, old-looking woman.

“I spoke to her, anyway, and said hello. No emotional feeling about her. Cold. No smile. She looked like a person to me that was in pain. Very hard to make conversation with her.

“I tried to hug her, but it was a cold hug I got from her. She wasn’t able to hug, or make contact.”

Father MacGréil recalls seeing judgement being passed on women in the past and says he is furious still with those people, but says he forgives them, “because they didn’t understand”.

He says the laundries were named for Mary Magdalene and were “supposed to be a place of sanctuary … But people didn’t understand the scriptural meaning behind it.”

Peter remembers the joy of first becoming a father, even as his mother withered away in the Magdalene Laundry: “I was so proud to be able to pick [my daughter] up, and hug her, and kiss her, and squeeze her into my body. The feeling was overwhelming.”

Peter used to bring his mother to the seaside: “And I handed the little baby over to her. She sat her on her knee and then I saw her smile. First time I saw her smile. And she was rocking her back and forth. That was a reminder of olden times, I would say, to her.

“I wanted to take her out to our own house, and I was stopped from doing that by the nuns, early on, a couple of years before she passed away, and they said you can’t do that, she’s institutionalised. That’s the word they used.

“We believed the nuns, we thought they were right. She was ‘the bad person’.”

(In writing this, I was uncertain whether Peter had said he wanted to bring his mother to “her own house” or “our own house”. I rang Peter and he said, quite emphatically: “Oh, our own house. We wanted her to come and live with us.”)

Father MacGréil says it bothers him that “it’s not accepted that the State is responsible. They blame the institutions, whether they were run by the Church, or other bodies, who were working for the State. The State is responsible for the welfare of its citizens, and it must acknowledge its role and it must pay. And this argument that people put forward that the religious orders should sell all their land and property. That wouldn’t be fair.”

With a laugh, Father MacGréil says: If the religious orders paid for the work they carried out for free, they would have nothing…

“It’s a terrible pity that it happened, but again that was the culture of the time.”

Ignoring the fact that there are today relatives of the Tuam Babies who don’t know if their loved ones are in the ground in Tuam’s disused septic tank, or alive in America, Father MacGréil says: “The sins of the past were the sins of the past. They did what they did because they believed it the right thing to do.

“We can’t try people from that era under the rules of today,” he says. However, MacGréil does acknowledge one thing.

“If it happened today, they would be in prison, I think.”

The nuns in Tuam forced nursing mothers to feed battery-lines of babies, to ensure they wouldn’t bond with their own babies. Imagine the sort of perversion that would dare to thwart nature, and worse, to try to kill love itself. The nuns in Tuam – and elsewhere – deliberately altered birth certificate details, knowing this would stymie efforts by mothers and their babies to reunite decades into the future. Imagine how evil you’d need to be to think of doing that.

The law of the land in 20th Century Ireland prohibited kidnapping, false imprisonment, enslavement, falsification of official documentation, illegal adoption, neglect, murder, and the improper disposal of human remains. Catholic institutions profited by the law not always being observed, however.

Of course, it’s not just the law of the land which puts the lie to the defence that we cannot judge the architects of the Tuam Home regime. A cursory glance at the Gospel shows that Jesus of Nazareth had some pretty strong words for those who would cause harm to children. In Matthew 18:6, Jesus says “it would be better for them to have a large millstone hung around their neck and to be drowned in the depths of the sea”. That is echoed, almost word-for-word in Mark 9:42 and in Luke 17:2.

The law of the land applied in Tuam, in the early 20th century, just as it does now. If you claim to be religious, the Gospel of the Lord applied too. The savagery, cruelty, and neglect experienced by children like Peter Mulryan proves neither the laws of God nor man were respected.