No, the Irish were not slaves, but there’s a reason the worst people want you to think they were, writes Donal O’Keeffe.

For the second year running, US President Donald Trump has declared March ‘Irish-American Heritage Month’. That will have gone down well with those North Carolina Trump supporters who told a Time reporter in 2016: “Irish slaves had it worse than Black slaves”.

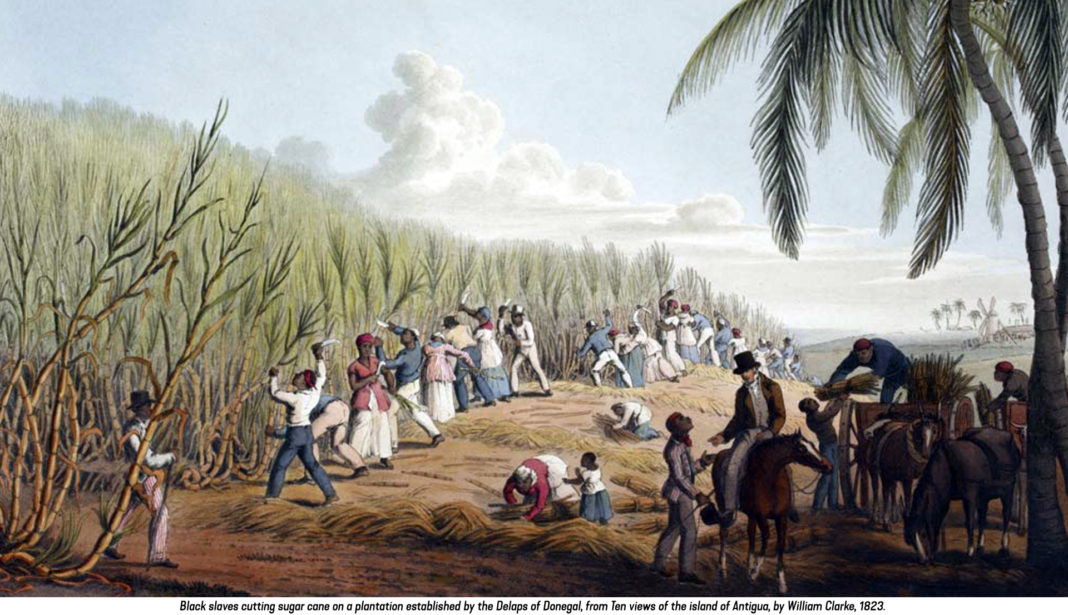

The ‘Irish slaves’ meme is a racist and discredited narrative based on an often deliberate conflation of indentured (and penal) servitude with chattel slavery. To explain this difference in a sentence, while indentured servants (and convicts) were considered to be human, chattel slaves (and their offspring) were considered property.

It’s important to note that by declaring March White History Month – I’m sorry, Irish-American Heritage Month – Trump is throwing a blatant rejoinder at February’s Black History Month. Black History Month began in the US as Negro History Week in 1926. The week was chosen to coincide with the February 12 birthday of Abraham Lincoln and the February 14 birthday of Frederick Douglass. If you really want an Irish-American history lesson, Douglass’ close friend Daniel O’Connell christened him ‘The Black O’Connell‘. In 1970, Negro History Week was redubbed Black History Month.

It’s also worth remembering that since 1987, March has been Women’s History Month in the US. Not that Donald Trump is renowned for his respect for either women or Black people.

You may have seen the recent recurring online claim that the Irish were America’s first slaves. The ‘Irish slaves’ lie is promulgated by white supremacists in an effort to belittle and denigrate the unique African-American experience of slavery, and it owes its origins, at least in part, to the work of the late Killavullen writer, Sean O’Callaghan.

The ‘white slavery’ claim has long been favoured by the far right, but O’Callaghan’s book “To Hell or Barbados (The ethnic cleansing of Ireland)” (O’Brien Press, 2000) was the first time the lie became specifically Irish. The book purported to tell the story of “the 50,000 men, women and children transported to Barbados and Virginia”, all of whom were “Irish slaves”, it maintained.

As Limerick librarian and historian Liam Hogan puts it, “The book was published as a piece of popular history. Nobody looked at it critically at the time.” Liam Hogan has been a key figure in challenging the online “Irish slaves” myth, and has received death threats for his troubles.

Hogan is scathing of O’Callaghan’s work, describing the book as shoddily researched, and calling O’Callaghan a well-meaning amateur who misread his sources and greatly overstated the numbers of Irish sent to the Caribbean in the Cromwellian period.

O’Callaghan’s book built on the racist fantasies of “They Were White And They Were Slaves: The Untold History of The Enslavement of Whites In Early America”, a self-published 1993 screed by Michael P Hoffmann II, a Holocaust denier who blames Jews for the African slave trade.

O’Callaghan expanded on Hoffmann’s claims, adding a salacious and entirely fictitious detail involving Irish women being forced to breed with African slaves. The depressing truth, of course, is that female African slaves were far more likely to have been raped by European men.

We know that European indentured servants – from all European empires operating the Caribbean – were forcibly deported to Barbados in the mid 17th century, where they endured appalling conditions. So terrible was their treatment, some observers were shocked into drawing an analogy to slavery.

During a visit to Barbados in 1654, the French priest Father Antoine Biet, noted that some white families were forcibly separated and their contracts were sold to different planters. Other first-hand accounts say servants lived in awful conditions and suffered the scantest diet, and were prodded with sticks if they didn’t work fast enough.

Horrible as all of that is, the key point to remember is that no matter how badly indentured servants and convicts were treated – and they were treated brutally – they remained in the law human.

African slaves were considered property, the equivalent of cattle. Not only were they the ‘property’ of their ‘masters’, but so too would their offspring be. That’s the key difference.

Another fact some would like forgotten is that many Irish benefitted from the lucrative slave trade. For instance, the Tuite (Tuitt) family originally from Westmeath were such significant slavers, including in the Danish West Indies, that at least two were made Chamberlains to the King of Denmark. So not only were we not slaves, in fact some of us were slavers. Small wonder we would prefer to perpetuate the lie of Irish enslavement.

The suggestion that African-Americans need to ‘get over’ what was done to them is deeply racist, and Irish people should be ashamed to be associated in it.

Dr Laura McAtackney is an associate professor in sustainable heritage management (archaeology) at Århus University, Denmark, and like Hogan, she has for years fought against the spread of the ‘Irish slaves’ myth. She questions the need for Trump’s Irish-American Heritage Month when Irish-Americans – unlike African-Americans – are no longer victims of discrimination.

“Uses of the past (and the reconfiguring of history) are always about and guided by the present, for good or ill,” McAtackney says. “Whereas in Ireland we often use the spectacle around St Patrick’s Day to expand and be inclusive in our definitions of what it is to be Irish (including floats representing recent migrant communities) and ‘Official Ireland’ uses it to promote Ireland and the inclusivity of Irishness around the globe, there is a sinister edge to how Irishness is being used in the contemporary US that has little to do with being Irish.

“Inadvertently or not, it is part of a wider movement that aims to diminish the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade and deny contemporary injustices still experienced by their descendants. We should not let our increasingly inclusive contemporary identity – and the accuracy of the histories we tell – be undermined and misused by white supremacists.”

Liam Hogan estimates conservatively that tens of millions of people have been exposed to ‘Irish slaves’ disinformation in one form or another on social media.

“These people, some of whom are Irish-American,” says Hogan, “are essentially digging up our ancestors’ bones and sharpening them into rhetorical weapons to use against people of colour.”

Visiting the United States for St Patrick’s week earlier this month, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar acknowledged a debt Ireland can never repay but should always honour.

During An Gorta Mór, when a million of us died and a million more took to the sea in coffin ships, strangers half a world away – strangers who had nothing themselves – rallied to our aid. In the depths of Black ’47, the worst year of our Great Famine, the Choctaw Nation gathered in Scullyville, Oklahoma and decided they had to help the starving Irish. They raised the equivalent in today’s money of about €4,000. These were people who had endured incredible hardship and who were living in dire poverty themselves.

Less than two decades earlier, the Choctaws had become – under President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act – the first Native Americans to be forcibly removed from their lands. Through the worst winter on record and through a cholera epidemic, some 17,000 Choctaws – men, women and children – were forced to walk the 500 mile Trail of Tears to Oklahoma. As many as 6,000 died en route. To quote choctawnation.com: “Only sixteen years had passed since the Choctaws themselves had faced hunger and death on the first Trail of Tears, and a great empathy was felt when they heard such a similar story coming from across the ocean… These noble Choctaw people, who had such meagre resources, gave all they could (to help) others in greater need.”

Trump, of course, used the occasion of White History Month – I must stop calling it that – to mention his pretend favourite president, the Irish-American Andrew Jackson. Trump references Jackson only because Steve Bannon gave him a pile of books – which America’s most proudly-ignorant president refused to read – but of course the openly-racist Trump found common cause with the architect of the Trail of Tears.

While it’s important to remember accurately the difference between the suffering experienced by the indentured Irish and that of African slaves, comparison (as opposed to conflation) is important. Empathy works by drawing comparisons. For example, it was similarities between the plight of the starving famine Irish and their own suffering that moved the Choctaw nation to action.

To honour the debt we can never repay to our Choctaw sisters and brothers, it’s vital no Taoiseach ever makes common cause with monsters like Trump, and his fake hero Jackson.