The notion that the Irish were America’s first slaves is a lie beloved of Donald Trump’s white supremacist supporters, and it was born in part in the heart of The Avondhu area.

Last week saw over 60 senior Irish-American leaders call for a boycott of ‘Irish Lives Matter‘ tee-shirts on sale in the US on Amazon and Walmart, with even the Ancient Order of Homophobes, er, sorry, the Ancient Order of Hibernians, accusing vendors of insulting ‘two heritages for one low price’.

In a letter sent to mark the passing of former congressman and Civil Rights giant John Lewis, current members of Congress Joe Kennedy III, Richard Neal and Brendan Boyle and former ambassadors, academic leaders and cultural figures, including novelist Colm Tóibín, wrote: “While some may try to excuse such tee-shirts as merely an exhibition of ethnic pride, we believe at best that they are tone deaf and insensitive, and at worst a deliberate, cynical attempt to trivialise, diminish or denigrate the Black Lives Matter. We urge Irish Americans to boycott these sales.”

While such honourable Irish-American leadership is of course to be applauded, the sleeveenism with the tee-shirts is only the latest manifestation of a long-running and disgusting equivocation about slavery, and a self-pitying whataboutery, from some in Irish-America, and nowhere is that agenda clearer than in the ‘Irish slaves’ meme ubiquitous on social media.

The ‘Irish slaves’ fantasy is a discredited narrative built on the deliberate conflation of African and African-American chattel slaves and Irish indentured servants, and it has become a boon to online white supremacists. Believe it or not, much of it started in the writings of a Killavullen native.

“White Irish slaves were treated worse than any other race in the US,” reads one of the hardiest canards on the internet. “When was the last time you heard an Irishman bitching that the world owes him a living?”

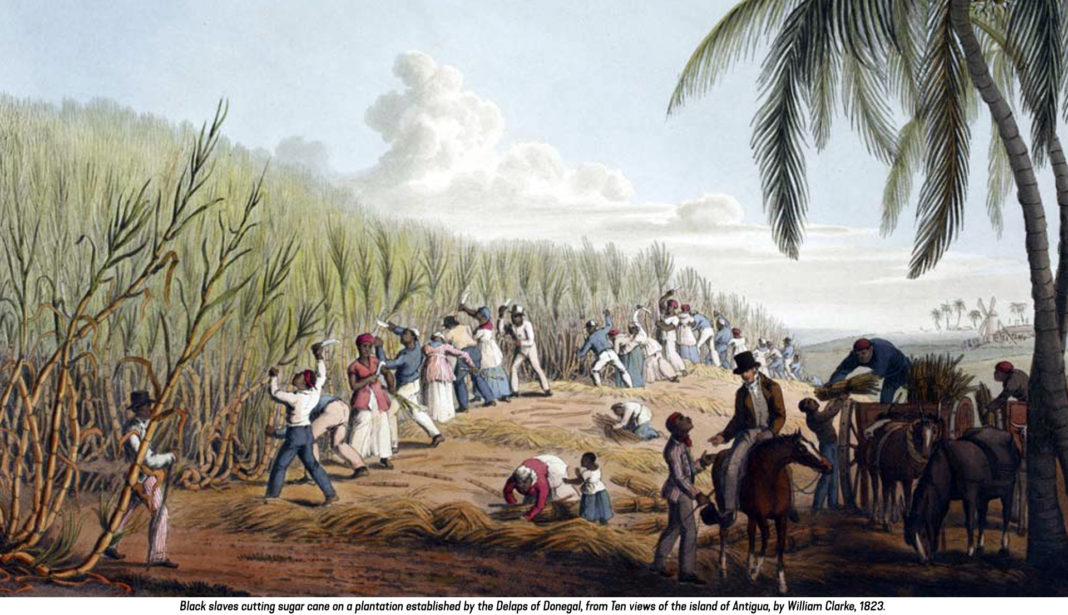

The myth of ‘Irish slaves’ purposely confuses indentured (and penal) servitude with chattel slavery, and it has been harnessed by racists to suggest that the African-American experience of slavery was not unique, that Irish people were treated worse, and that socio-economic conditions suffered by modern-day African-Americans are the result not of a legacy of racial abuse, but rather of racial inferiority.

The simple truth about the difference between indentured (and penal) servitude and perpetual, hereditary chattel slavery can be explained in a sentence: While indentured servants (and convicts) were treated brutally, they were considered in law to be human, whereas chattel slaves (and their offspring) were considered property.

The notion of ‘Irish slaves’ is a lie promulgated by white supremacists in an effort to belittle and denigrate African-Americans, and it owes its origins at least in part to the work of the late Killavullen writer, Sean O’Callaghan.

‘White slavery’ had long been favoured by the far right, but O’Callaghan’s book To Hell or Barbados (The ethnic cleansing of Ireland) (O’Brien Press, 2000) was the first time that the lie became specifically Irish. O’Callaghan’s book purported to tell the story of “the 50,000 men, women and children transported to Barbados and Virginia”, all of whom were ‘Irish slaves’, it maintained.

As Limerick librarian and historian Liam Hogan puts it: “The book was published as a piece of popular history. Nobody looked at it critically at the time.” Hogan has been a key figure in challenging the online spread of the ‘Irish slaves’ myth, and he has received death threats for his troubles.

Hogan is scathing of O’Callaghan’s work, describing To Hell or Barbados as shoddily researched, and calling O’Callaghan a well-meaning amateur who misread his sources and greatly overstated the numbers of Irish sent to the Caribbean in the Cromwellian period.

O’Callaghan’s book built on the racist fantasies of ‘They Were White And They Were Slaves: The Untold History of The Enslavement of Whites In Early America’, a self-published 1993 screed by Michael P Hoffmann II, a Holocaust denier who blamed Jews for the African slave trade.

O’Callaghan expanded on Hoffmann’s claims, adding a salacious and entirely fictitious detail involving Irish women being forced to breed with African slaves. The depressing truth, of course, is that female African slaves were far more likely to have been raped by European men.

We know that European indentured servants – from all of the European empires operating in the Caribbean – were forcibly deported to Barbados in the mid-17th Century, where they endured appalling conditions. So terrible was their treatment, some observers were shocked into drawing an analogy to slavery. During a visit to Barbados in 1654, French priest Father Antoine Biet noted that some white families were forcibly separated and their contracts were sold to different planters. Other first-hand accounts say servants lived in awful conditions and suffered the scantest diet, and were beaten savagely if they didn’t work fast enough.

Horrible as that is, the key point is that no matter how badly indentured servants and convicts were treated – and they really were treated brutally – they remained in law human. Their servitude ended with their contracts, or their sentences, if they survived.

African slaves were considered property. They could be raped, murdered or worked to death, and no punishment would accrue to their assailants. Not only were they the ‘property’ of their ‘masters’, but so too would be their offspring. That’s the key difference.

Another fact some might prefer forgotten is that many Irish benefitted from the lucrative slave trade. For instance, the Tuite (Tuitt) family originally from Westmeath were such significant slavers, including in the Danish West Indies, that at least two were made Chamberlains to the King of Denmark.

Dr Laura McAtackney is associate professor of Archaeology and Heritage at Århus University, Denmark, and – like Hogan – she has for years fought against the spread of the ‘Irish slaves’ myth.

“Uses of the past (and the reconfiguring of history) are always about and guided by the present, for good or ill,” McAtackney says. “Whereas in Ireland we often use the spectacle around St Patrick’s Day to expand and be inclusive in our definitions of what it is to be Irish (including floats representing recent migrant communities) and ‘Official Ireland’ uses it to promote Ireland and the inclusivity of Irishness around the globe, there is a sinister edge to how Irishness is being used in the contemporary US that has little to do with being Irish.

“Inadvertently or not, it is part of a wider movement that aims to diminish the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade and deny contemporary injustices still experienced by their descendants. We should not let our increasingly inclusive contemporary identity – and the accuracy of the histories we tell – be undermined and misused by white supremacists.”

As Donald Trump faces a re-election campaign dominated by his own criminal mismanagement of Covid-19, and at a time when the US economy is in the toilet, he has clearly set his stall on opposing the Black Lives Matter movement in the desperate hope to fire up his shrinking base.

Trump learned this at the knee of his racist father, Frederick Christ Trump. In 1989, Donald Trump, then a property developer, took out full-page newspaper advertisements demanding the return of the death penalty for the five Black and Hispanic teenagers (aged between 14 and 16) falsely accused of raping Trisha Meili, a white woman, in Central Park.

In 2008, when he was most famous for playing a businessman on television, Trump helped launch the racist ‘Birther’ movement, which claimed falsely that Barack Obama was ineligible to be US president because he was born in Kenya. (Obama was born in Hawaii.)

At the heart of the ‘Irish slaves’ myth is the suggestion that the Irish survived worse conditions than African-Americans, and afterwards thrived, and thus current socio-economic conditions suffered by African-Americans are the result not of the legacy of chattel slavery, America’s original sin, but rather are caused by innate inferiority.

As November’s election nears, and Trump’s racism becomes ever-more overt, expect to see a lot more of the ‘Irish slaves’ meme online. Liam Hogan estimates conservatively that tens of millions of people have already been exposed to disinformation spread by white supremacists.

“These people, some of whom are Irish-American,” says Hogan, “are essentially digging up our ancestors’ bones and sharpening them into rhetorical weapons to use against people of colour.”