You mightn’t know it, but today is National Franklin Day. Donal O’Keeffe looks at the touching story behind a minor, but important, comic-book character.

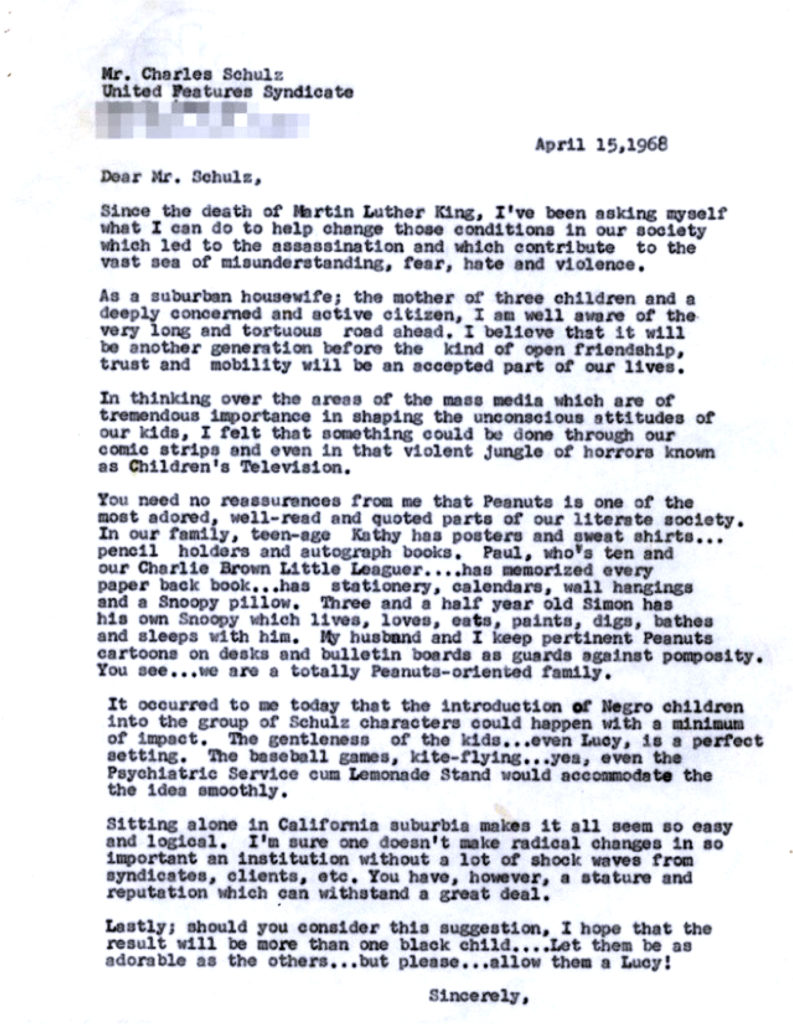

On April 15, 1968, a Los Angeles schoolteacher named Harriet Glickman wrote a letter to Charles M. Schulz. Schulz was the creator of the nationally (and internationally) syndicated comic-strip Peanuts, home to Charlie Brown and Snoopy. He was – to use a modern term – box office, and Mrs Glickman probably did not expect a reply.

“Dear Mr Schulz,” she wrote, “Since the death of Martin Luther King, I’ve been asking myself what I can do to change those conditions in our society which led to the assassination and which contribute to the vast sea of misunderstanding, fear, hate, and violence.

“As a suburban housewife; the mother of three children and a deeply concerned and active citizen, I am deeply aware of the long and tortuous road ahead. I believe that it will be another generation before (any) kind of open friendship, trust and nobility will be an accepted part of our lives.

“In thinking over the areas of the mass media which are of tremendous importance in shaping the unconscious attitudes of our kids, I felt that something could be done through our comic strips …

“… It occurred to me today that the introduction of Negro children into the group of Schulz characters could occur with a minimum of impact. The gentleness of the kids… even Lucy, is a perfect setting. The baseball games, kite-flying …

“Sitting alone in California suburbia makes it all seem so easy and logical. I’m sure one doesn’t make radical changes in so important an institution without a lot of shock waves from syndicates, clients, etc. You have, however, a stature and reputation which can withstand a great deal.

“Lastly; should you consider this suggestion, I hope that the result will be more than one black child… Let them be as adorable as the others… but please… allow them a Lucy!

Sincerely,

Harriet Glickman.”

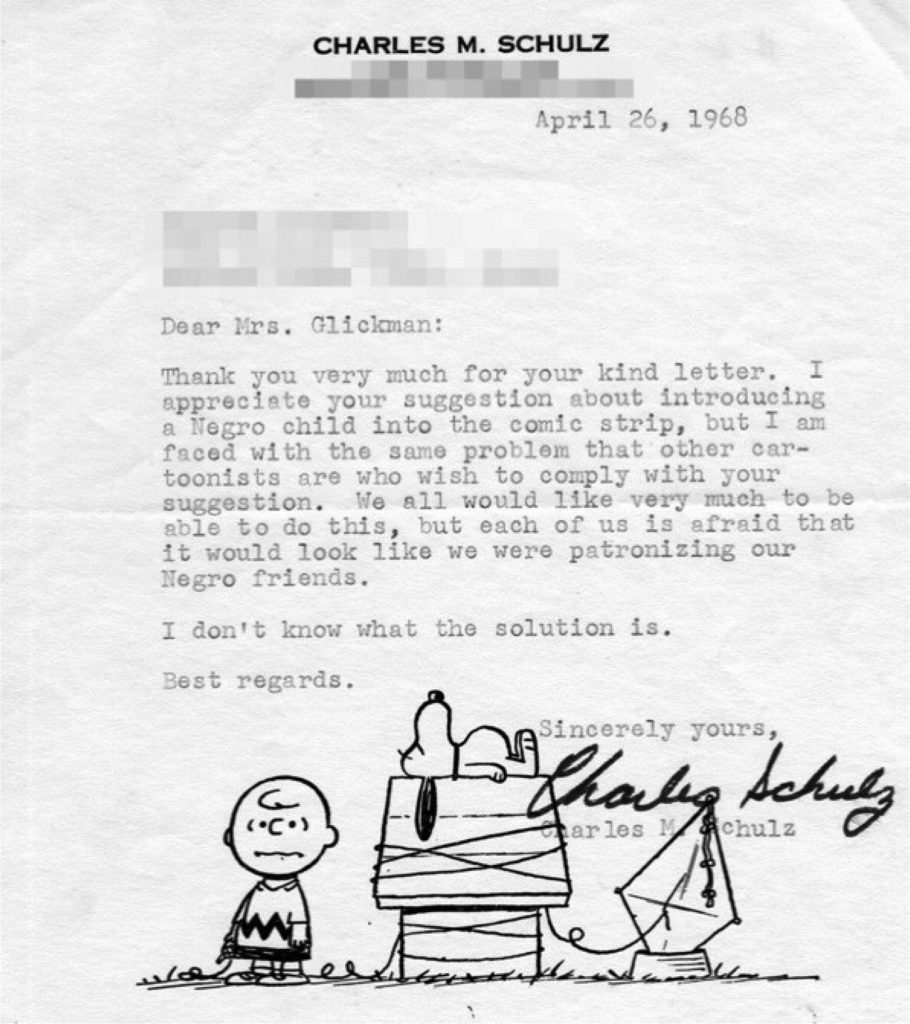

Box office or not, Schulz replied.

“Dear Mrs Glickman,

“Thank you very much for your kind letter. I appreciate your suggestion about introducing a Negro child into the comic strip, but I am faced with the same problem that other cartoonists are who wish to comply with your suggestion. We would all like very much to be able to do this, but each of us is afraid that it would look like we were patronizing our Negro friends.

“I don’t know what the solution is.

“Best regards.

Sincerely yours,

Charles M. Schulz.”

Undaunted, Mrs Glickman replied, in a letter dated April 27, 1968, saying “You present an interesting dilemma.

“I would like your permission to use your letter to show some Negro friends. Their response as parents may prove useful to you in your thinking on this subject.”

Schulz replied on May 9, sounding even less enthusiastic.

“I will be very anxious to hear what your friends think of my reasons for not including a Negro child in the strip. The more I think of the problem, the more I am convinced that it would be wrong for me to do so. I would be very happy to try, but I am sure that I would receive the sort of criticism that would make it appear I was doing this in a condescending manner.”

Glickman then gathered letters from African-American parents, all telling Schulz they would be delighted to see a black character in Peanuts.

The letters urged Schulz to create a character, in a situation that depicted racial friendship, suggesting that it was not only important for their children to see themselves depicted more accurately, but also to help break the media’s regular exclusion of minorities in everyday scenes.

“At this time in history, when Negro youths need a feeling of identity; the inclusion of a Negro character even occasionally in your comics would help these young people to feel it is a natural thing for Caucasian and Negro children to engage in dialogue,” wrote one anonymous mother of two.

On July 1, 1968, Charles Schulz wrote back to Harriet Glickman. (He misnamed her “Mrs Glukman” in the letter, but I suspect she forgave him his mistake.)

“You will be pleased to learn that I have taken the first step in doing something about presenting a Negro child in the comic strip in the week of July 29. I have drawn an episode which I think will please you.

Kindest regards.

Sincerely yours,

Charles M. Schulz.”

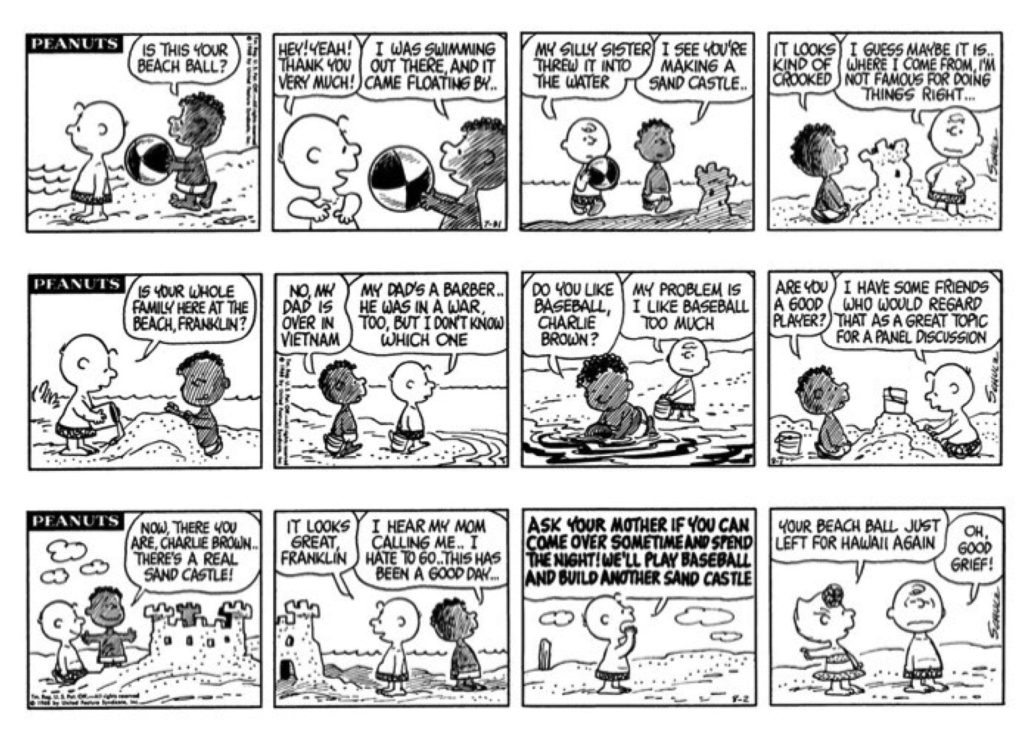

On July 31, 1968, Peanuts featured Charlie Brown playing on the beach, building a sandcastle with his customary lack of skill. A little African-American boy returns to Charlie Brown his beachball, which the boy, Franklin Armstrong, says he found floating in the sea. Charlie Brown explains that his little sister, Sally, had thrown the ball in the water.

The kids chat about baseball, and Franklin mentions that his dad is in Vietnam. This would have been topical, as the Vietnam War was the first major American conflict in which the army was integrated. Black soldiers had fought in previous wars in segregated units.

Corry Kanzenberg, curator of the Schulz Museum, has said it was very unusual for the cartoonist, who prided himself on being the sole creator behind Peanuts, to base such a decision on a fan’s suggestion.

Franklin’s initial, three-day run was met with a broadly positive reaction, but some southern editors and newspapers refused to carry the strip.

Franklin soon became a series regular. Some controversy erupted when Schulz depicted Franklin as a classmate of Peppermint Patty. School segregation was, at the time, still an issue. Schulz ignored his critics.

Schulz recalled “one southern editor who said something about ‘I don’t mind you having a black character, but please don’t show them in school together’.

“But I didn’t even answer him.”

When Larry Rutman, president of the United Features syndicate, Schulz’s boss, complained about Franklin, and suggested the character be removed from the strip, Schulz gave him a blunt answer.

“Well, Larry, let’s put it this way: Either you print it just the way I draw it or I quit. How’s that?”

As Schulz said later, “So that’s the way that ended.”

Franklin has always been kinder than other characters, never criticising or mocking Charlie Brown.

Some have argued that the niceness of Franklin’s character is – just as Schulz feared – patronising, and it’s probably fair to say that having introduced such a ground-breaking character, Schulz never quite seemed to know what to do with him.

Still, Franklin’s debut in Peanuts was, for its time, a hugely important development in the representation of black characters in American popular culture, and, in 2015, Peanuts declared July 31 National Franklin Day.

A few years ago, Harriet Glickman confessed that she had had no idea the effect her letter to Charles M. Schulz would have, but in the wake of the assassination of Dr Martin Luther King Jr, she had felt she couldn’t give in to helplessness.

“You wanted to do something: you felt powerless in a situation like that. I thought, ‘This might be a nice little idea.’”

Happy National Franklin Day.

(Images courtesy of the Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Centre, Santa Rosa, California.)