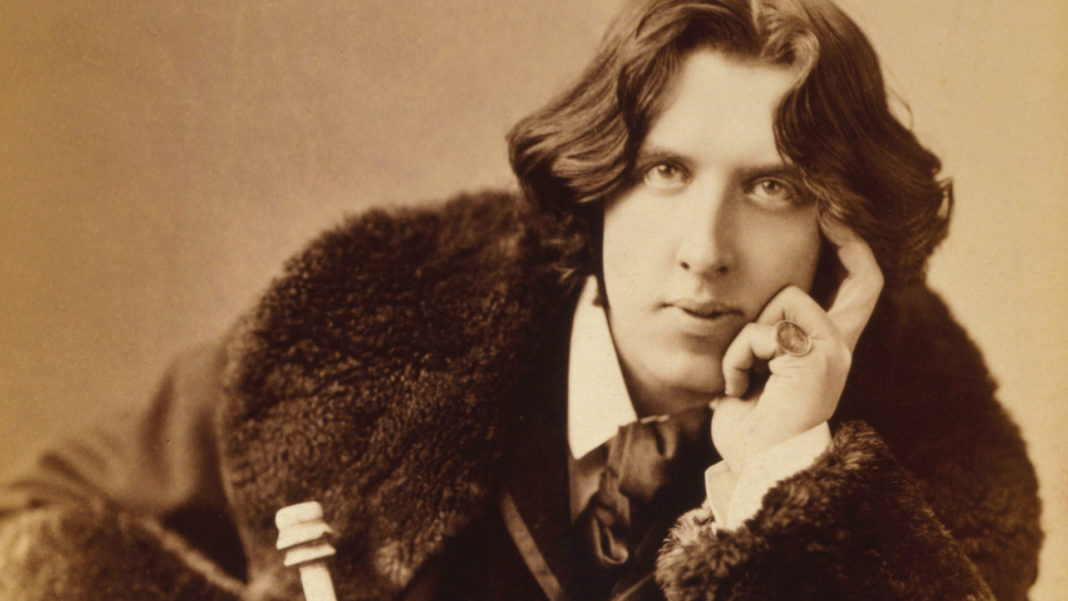

All art is quite useless, according to Oscar Wilde.

If your first instinct is to follow that line with “Turner 1775 to 1851”, then you are a person of exquisite taste and a friend of mine.

But no, I’m not quoting A House’s 1992 indie classic 'Endless Art', although in doing the sort of rigorous, in-depth research associated with this column (Wikipedia), I was intrigued to find the band had responded to accusations of sexism (all of the artists mentioned in the song were male) by recording a new version called 'More Endless Art', referencing female artists.

Wikipedia notes drily that while “the substitution of ‘Walt Disney’s Minnie Mouse’ for his Mickey Mouse may not quite right the gender balance … ‘More Endless Art’ was better than a defence Dave Couse had offered in interviews, that the band had thought that Joan Miró was a woman.”

The phrase “all art is quite useless” appears in the preface to Oscar Wilde’s only novel, 'The Picture of Dorian Gray'. It so intrigued an Oxford University student named Bernulf Clegg, that in 1891 he wrote to Wilde asking him where in his other work he “may find developed that idea of the total uselessness of all art.”

Not quite answering the question, Wilde replied:

“My dear Sir

“Art is useless because its aim is simply to create a mood. It is not meant to instruct, or to influence action in any way. It is superbly sterile, and the note of its pleasure is sterility. If the contemplation of a work of art is followed by activity of any kind, the work is either of a very second-rate order, or the spectator has failed to realise the complete artistic impression.

“A work of art is useless as a flower is useless. A flower blossoms for its own joy. We gain a moment of joy by looking at it. That is all that is to be said about our relations to flowers. Of course man may sell the flower, and so make it useful to him, but this has nothing to do with the flower. It is not part of its essence. It is accidental. It is a misuse. All this is I fear very obscure. But the subject is a long one.

“Truly yours, Oscar Wilde.”

The first time I saw Van Gogh’s Chair in London’s National Gallery, I was so mesmerised by the thickness of Vincent’s painting, and by the strange angles he used, I felt I could almost reach out and touch the three-dimensional chair inches from me.

I will never be able to buy a Van Gogh, which is ironic, given that poor Vincent was in his lifetime never able to sell a Van Gogh, but I will always have the memory of feeling in some magical way connected to his painting.

It’s strange the ways we form connections with works of art.

I would probably love Julie Feeney’s extraordinary 2012 album 'Clocks' no less if the artist hadn’t sent me a signed copy on vinyl, but having the album, seeing my name in the credits, playing it on my turntable, has made me feel all the more attached to it.

Liz Nugent’s little nod to me in the dedication at the back of her superb novel 'Lying in Wait' didn’t change the brilliance of her writing a jot, but it did make me cherish my copy that bit more. (Especially when, at the launch, I spilled my drink on it and Liz dubbed it 'Lying in Wine'.)

I’ve written about the Tuam Babies since Alison O’Reilly first broke the story in 2014. I would have found her book 'My Name is Bridget' staggering regardless, but her mentioning me in it was as one of the honours of my life.

I’ve been a Bob Dylan fan most of my life, but like many, I had long ago decided I didn’t need to see him play live ever again. I had only ever seen his indifferent, scowling, uninterested performances, and had decided I would stick to listening to his albums. Then, in 2014, I won a pair of tickets to see him play the Marquee in Cork. I brought my eldest nephew with me, telling him the concert would be terrible, but he could always say in years to come that he had seen Bob Dylan.

To my astonishment, the gig was sublime. Bob was in fine fooling, and having a whale of a time. My nephew enjoyed the gig, and said afterward I had been very hard on Bob.

I had been at the front of the stage, and there was one glorious moment during his jaunty performance of ‘Duquesne Whistle’ when my enjoyment was immeasurably improved because, for a second, I saw Bob Dylan actually smile.

I’ve loved my Bob albums all the more ever since.

My album sleeves are crumpled and damaged, and my books are creased and tattered. My DVDs could never be resold. What’s left of my comic collection is damaged and lonesome-looking.

If anyone were to appraise for resale my most prized possessions, they would probably say they were all worthless. But like the businessmen who drank Bob Dylan’s wine, and the ploughmen who dug his earth, “none of them along the line know what any of it is worth.”

It’s the same for everyone. We all have a favourite song, or a hundred favourite songs, or a treasured book, or a movie we’ve seen a dozen times. Maybe it’s a tune you heard on the happiest day of your life, or the saddest. Maybe it’s a poem you cling to for dear life. Maybe it’s the Christmas film you watched the last Christmas ever your family was together.

“What shall we do?” asked Elvis Costello, “What shall we do, with all this useless beauty?”

Oscar is right, of course. The purpose of art is to make us feel. If you live in a utilitarian world, you will never appreciate beauty. You’ll know price and no value.

All art is quite useless.

Good.